Hunt and Lauda. What I wrote at the time. The Guardian 25 October, 1976.

No writer of fiction would have dared drag out the suspense of a world motor racing championship to the closing minutes of a year long, 16 race series. The final laps in the Grand Prix of Japan, when it looked as though Niki Lauda might keep the title as James Hunt’s McLaren suffered tyre trouble, contained the sort of drama only expected in a Frankenheimer movie.The blond hero did not win the race, but he won the cham-pionship, while the battle scarred Austrian, who had seemed unassailable in June, retired

because he couldn’t see through Fuji’s October fog. It was a brave decision. He returns to Europe for an operation to an eyelid which still does not close, a legacy of his Nürburgring injuries.

The season’s acrimony and protests will not be forgotten. The legal wrangles may have failed to get Lauda the drivers’ title, although they did gain Enzo Ferrari the constructors’ championship which, for the 78 year old Master of Maranello, is probably more important. His attachment to his cars is emotional and he remains the most powerful man in motor racing, Bernie Ecclestone and the Formula One constructors notwithstanding. They are no match for Ferrari, who directs events by remote control without ever leaving his shuttered industrial fortress on the plains of Lombardy.

Lauda’s courage will be remembered longer than his cavalier attitude towards the press, and the enthusiasts who tried to meet him or, pursue him for his autograph. The most they usually see is the closed door of his caravan,- or his helicopter as he flies back for more testing at Fiorano. Here, he hones his cars to perfection, and the moment he stops, as after his accident, their edge is lost.

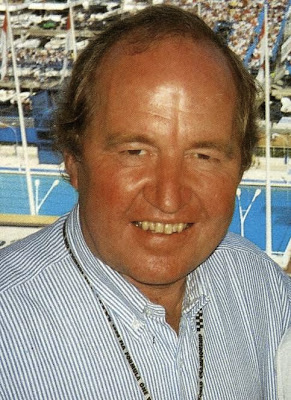

James Hunt will be remembered for a calmness and maturity surprising to those who knew him in his early days. He is accessible, entertaining, and seems to drive racing cars because he enjoys it. No cool technician like Lauda, who may have his head and his heart in his driving, Hunt has his soul in it.

It is difficult not to draw a comparison between Hunt and Britain’s first world champion, Mike Hawthorn. Hunt has the same boyish good looks, the same easygoing manner, and the same sort of zest. You could never picture Jackie Stewart with a pint in his hand; there was never anything boisterous about Jack Brabham. Denny Hulme was positively monastic. Hunt’s talent is like Hawthorn’s, at its best against the odds and enjoying a challenge, and although occasionally inconsistent it stems from a natural athletic urge.

He is different from Jim Clark, who was shy and retiring. Clark’s talent amounted to genius, and he would take whatever car he was given and make it go faster than anyone else in the world; his sense of balance and accuracy of vision were so highly developed that he adjusted to the car not the other way round.

Jackie Stewart had natural talent too, but it was focused more on making the car suit him. His gift was precise communication with his engineers. He could describe how the car behaved and would have it constantly improved.

Graham Hill was a man of iron will, who won races with more courage and determination than inborn skill at the wheel. Like Lauda he recovered from a terrible accident, but Lauda added an understanding of the complex electronic test facilities Ferrari employs to match the car to each circuit before it reaches the start line.

Jack Brabham was a talented engineer, who knew his car’s theoretical limitations and would calmly experiment as he drove until he established what they were in practice. He almost invented the science of chassis tuning, adjusting ride height, spring rates and so on 17 years ago. John Surtees, champion in 1964 for Ferrari, was another practical driver, perhaps relying even more than Brabhani on how the car felt through the seat of his pants.

There will be no monasticism for the new world champion. He keeps in training, but by inclination, not stricture. He will be a successful ambassador for his country and for motor racing, with all the qualities of a classic schoolboy hero.

In an interview after the Japanese Grand Prix Lauda defended his decision to pull out of the race after two laps. “There is a limit in any profession or sport,” he said. “The cars are not suitable for driving through so much water. When logic tells you that things will not work right, to me it is the normal human reaction to draw the inevitable conclusion, not to say ‘I hope for a miracle’ - and a miracle it was, in my opinion, that there were no fatal accidents.”

FINAL WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP POSITIONS. Hunt (GB) 69, Lauda (Austria) 68, Scheckter (S. Africa) 49, Depaillier (France) 39, Regazzoni (Switzerland) 31, Andretti (US) 22, Lafitte (France) 20, Watson (N. Ireland) 20, Mass (Germany 19, Nilsson (Sweden) 11, Peterson (Sweden (10) Pryce (GB) 10, Stuck (Germany) 8, Pace (Brazil) 7, Jones (Australia) 7; Reutemann (Argentina) 3. Amos (NZ) 2, Stommelen (Germany) 1, Brambilla (Italy) 1.

Following the film RUSH and the

Motor Sport retro video the BBC repeated its splendid Hunt/Lauda documentary last night with Simon Taylor, one of the stars of the film, who said “This is indeed a completely new documentary. It includes fresh interviews with Daniele Audetto, Alistair Caldwell, Niki himself, even James’ sister (who has never appeared talking about her brother before, apparently). I have only been allowed to see snatches, but they were enough to indicate that the researchers have managed to find some remarkable footage from 1976 that was new, as well as the old familiar stuff.”

I was motor racing correspondent of The Guardian at the time. Italian newspapers took up what they perceived as criticism of Enzo Ferrari, and he basked in the view of himself as influential as Bernie Ecclestone. He responded personally to me the following year. I framed the letter.