The D-type is on display in Duns. TKF9’s place is secure. Autocar featured XKD517 E2026-9 in its original pastel green at Oulton Park. Champion recalled it in white when the “pirates de la frontière” bought it for Jim Clark. Michael Cooper photographed me at the wheel on the memorable test day.

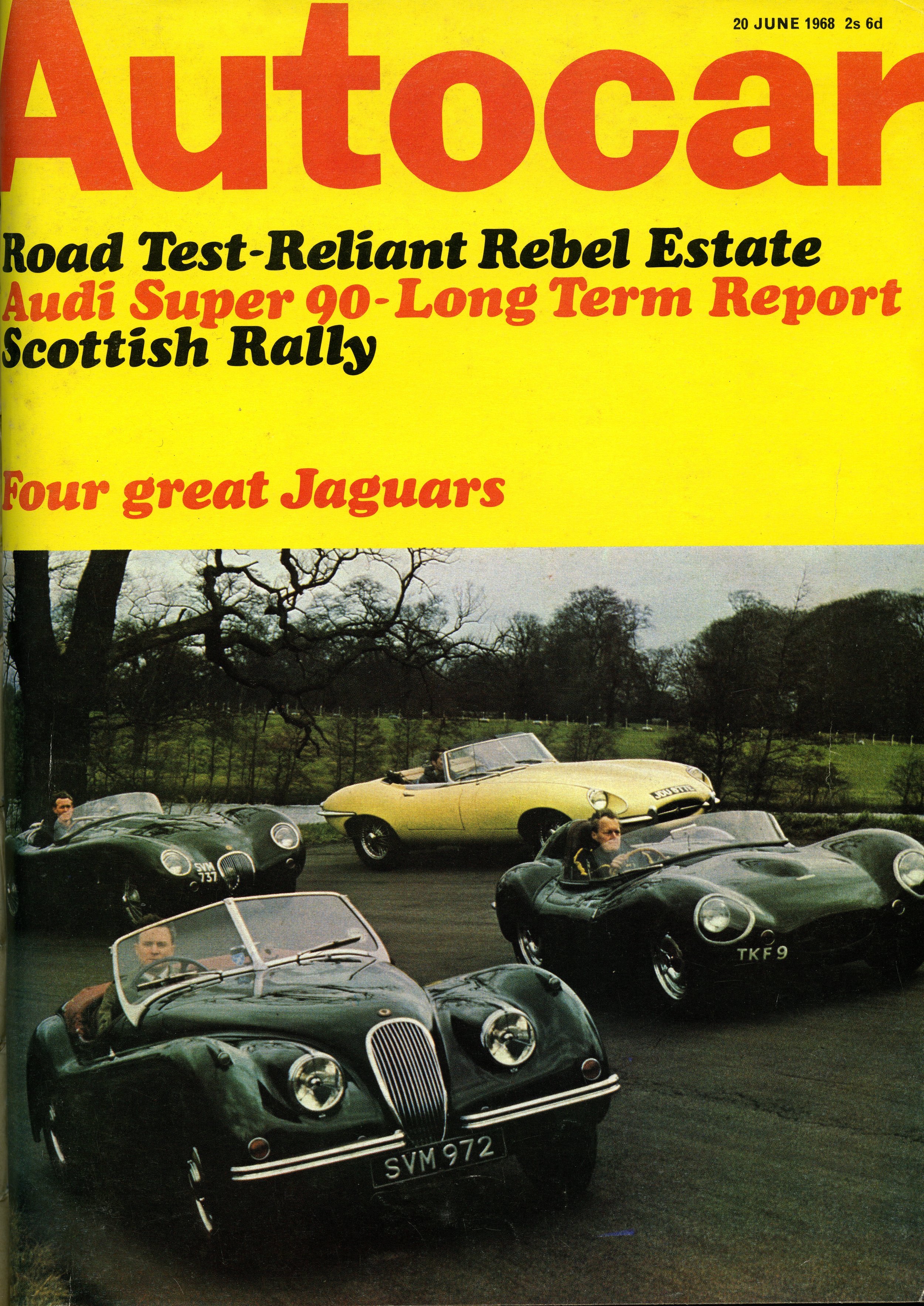

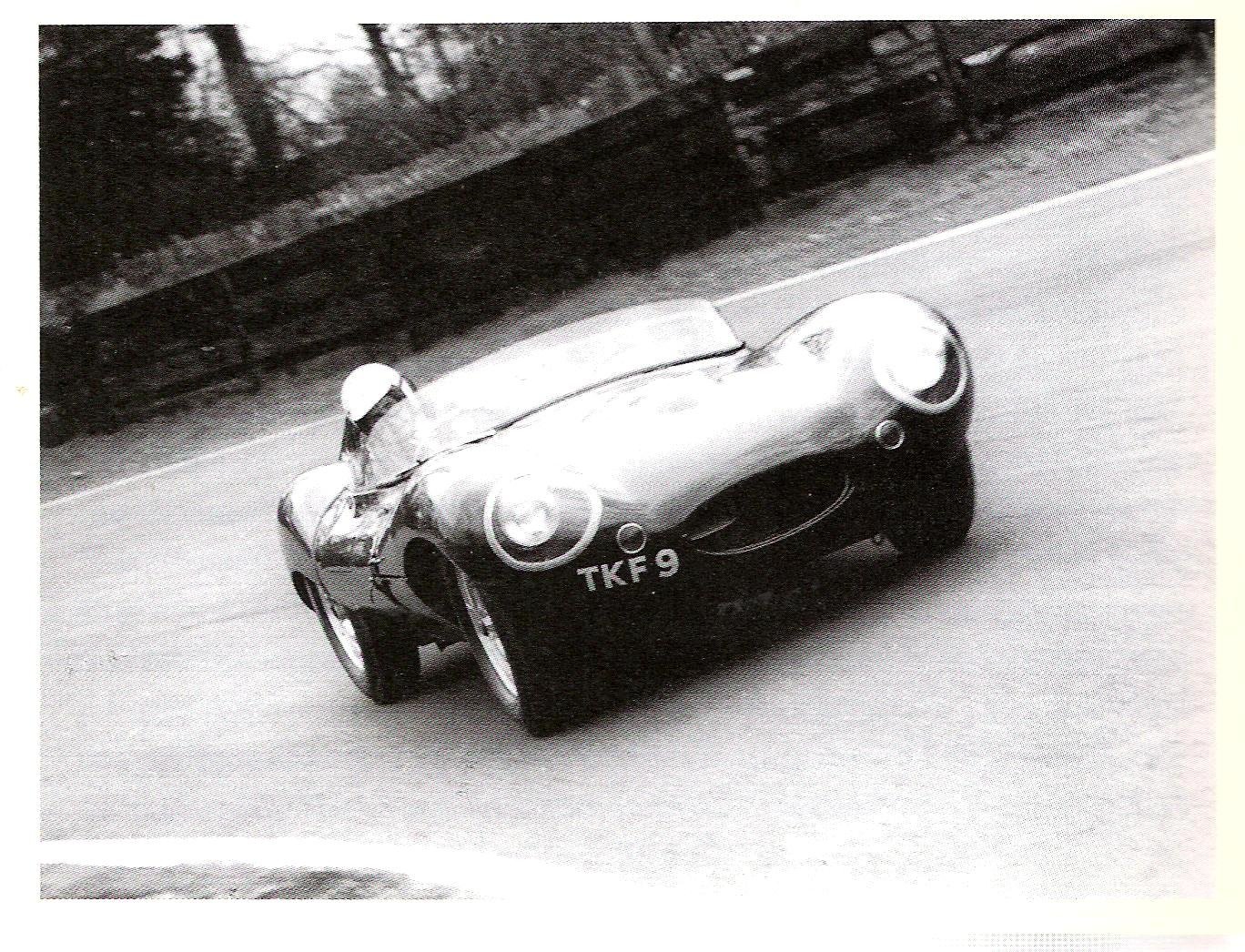

TKF9 was 13 years old when I got my hands on it. Not long after Clark’s death Andrew Whyte, of Jaguar’s press office, organised a day’s testing of the Bryan Corser collection at Oulton Park along with a works E-type: “A good D-type is such a collector's item that when one does come on the market, upwards of £5,000 is likely to change hands,” I wrote in 1968.

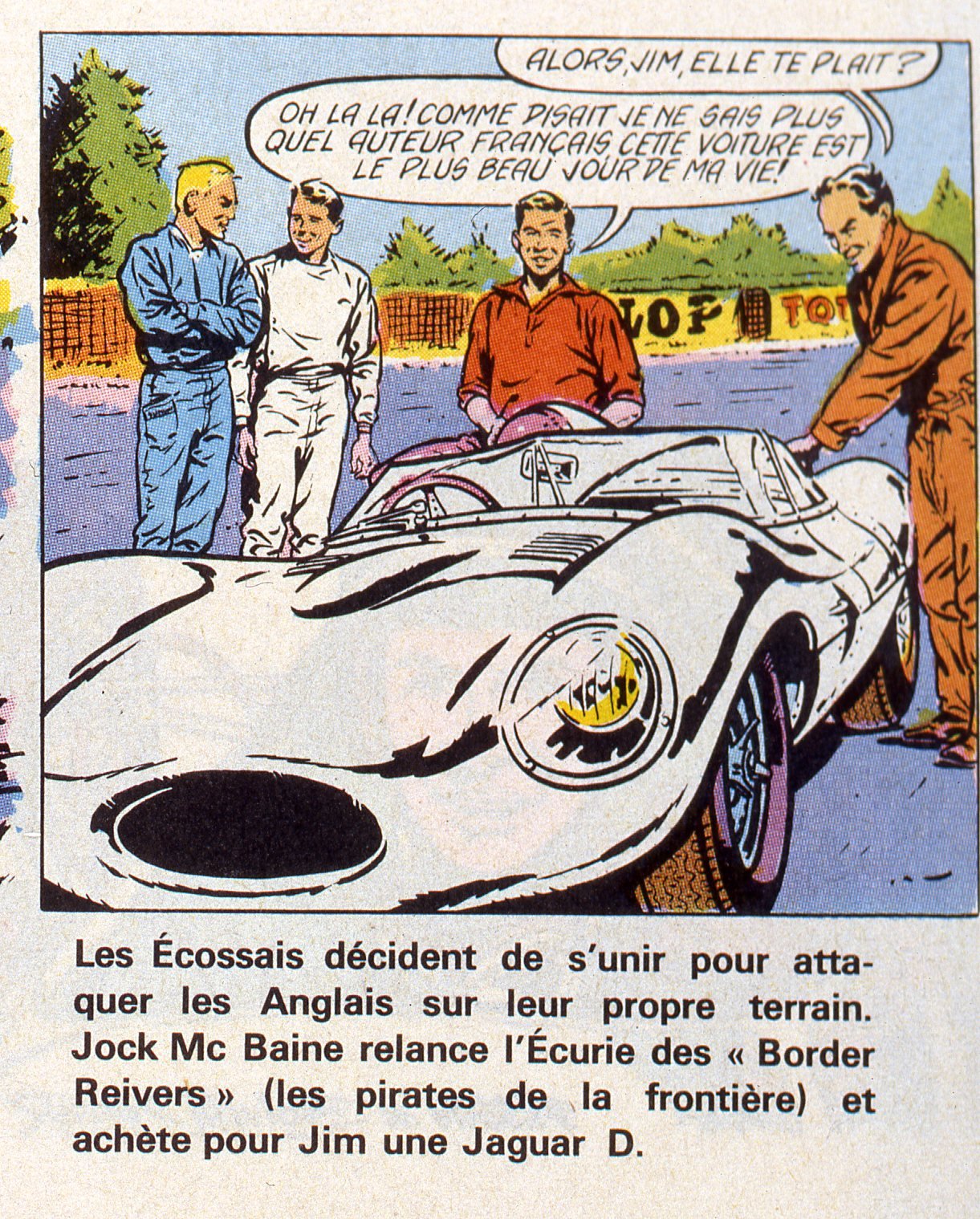

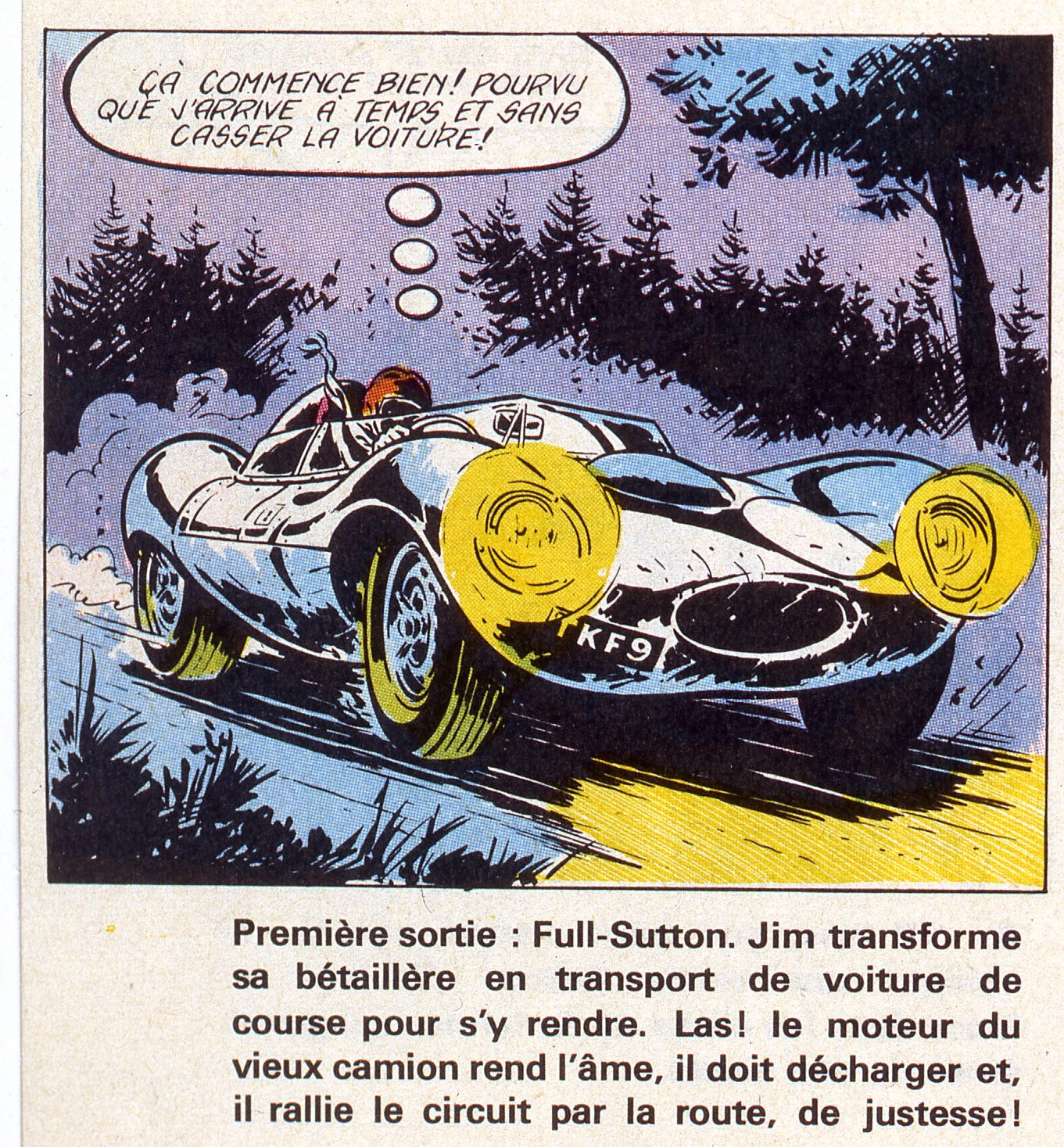

Originally sold to Gillie Tyrer, successful Frazer Nash BMW driver in 1955, it passed to Murkett Brothers for Henry Taylor to race (and crash) before Autosport advertised it for sale. Clark told Graham Gauld: “I thought (the Reivers) were daft asking me to drive it. I told them it was too quick for me, but they persuaded me to try it out at Charterhall. All I did was take it up and down the straight, for the track wasn't even open and it scared me to death. I thought it extremely fast. At Full Sutton I knew I was not going to just run up and down a straight but take it round corners as well. I couldn’t equate its handling. I just didn't know anything. It was difficult, although it taught me quite a bit. It had bags of power and provided plenty of sideways motoring.”

Champion’s glee with Jim Clark knew no bounds. Boivent Duffar depicted the 22-year old’s chilling experience. Forced to abandon his bétaillère en transport (farm-lorry) for his voiture de course. Clark drove through a frosty night into the record books. At Full Sutton, near Pocklington in Yorkshire, he was the first sports car driver to average 100mph on a British circuit. The expedition is detailed on page 77 (above) of Jim Clark, Tribute to a Champion, ISBN 978-0-9574585-5.0 also on sale at the museum or through the Jim Clark Trust website.

D-Types had a magnesium central section, a front tubular sub-frame of steel, not aluminium. The engine was dry-sump with no proper flywheel, making-do with a crankshaft damper and the mass of a triple-plate clutch. With 285 bhp on three Weber carburettors, a 2.79:1 axle, and 6,000 rpm (only 250 rpm above peak power) it would do 183 mph. TKF9 was a 1955 production D with short nose and a head fairing but no fin. Corser thought a fin would look nice but wouldn't be genuine.

Climbing in through the tiny, fragile door felt like getting into a space capsule, close fitting, fully instrumented, functional. The leather was soft, the seat hugged me, I thought the view over the front like a bulgy E-type. Superficially it did feel like an E, smooth ride, the easy way you could power out of corners yet keep a firm grip of the road. The rear suspension was hung on the back much like the C-type I drove that day but with different trailing arms.

Track driving, I found made me oddly sensitive to smells. A whiff of hot oil on the straights, pungent rubber dust, the acrid scent of hot brakes coming up to corners reminded me these were racing cars. You sensed, saw, felt everything. The hard blare of noise from the exhaust set adrenalin running, especially if you tried changing your mind halfway through Druids. No car was more clearly a racer, yet it was almost polite against the down-to-earth harsher C-type.

Gear ratios were close and the change, quite un-Jaguar-like for 1955, superb. Using the brakes was like pressing a small, hard rock but how well they worked, again and again without fading. The D-type was exciting although perhaps less well suited than the C-type to tight, slow corners at Oulton Park than long fast ones. This was a car for a fast circuit with steering sensitive, cornering progressive and predictable. The good manners of Dunlop racing tyres and splendid balance of the D meant you could break it away at the front or the back or on all four wheels at once if you wanted to. It did as I told it, no more, no less.

After XKs that you sat on, rather than in, the stricter but tighter C-type, and that historic D the E-Type did feel just a little soggy on a track. Yet a comparison would not be fair. This was a refined, stable, predictable road E and when I took it back on the highway it was easier to see where the good points of the D had rubbed off. The stiff hull, the smooth ride, the way you could apply power and keep supreme control in wet or dry was a clear legacy of all the great racing Jaguars.