Motor racing threw up some notable writers. SCH Davis, Bentley Boy of the 1920, sports editor ofThe Autocar over 40 years. Rodney Walkerley, his urbane, witty opposite number at The Motor. Bill Boddy, longest serving editor of Motor Sport; Denis Jenkinson its Continental Correspondent and co-pilot with Moss in the Mille Miglia. Gregor Grant, Autosport founder who never let the facts stand in the way of a good story. The engaging American Henry B Manney III, as funny in life as in print. Peter Garnier, Davis’s astute successor, so close to his subject they made him secretary of the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association. Innes Ireland, amazingly articulate and perceptive at Autocar, paving the way for television punditry from James Hunt, Martin Brundle and David Coulthard. Elegant technicians, Laurence Pomeroy son of the gifted Vauxhall designer and LJK Setright, whose classical quotations were almost as good as Pom’s but whose engineering was no match. We had the well-informed David Phipps and nowadays Alan Henry and spirited prose from Maurice Hamilton and Peter Windsor.

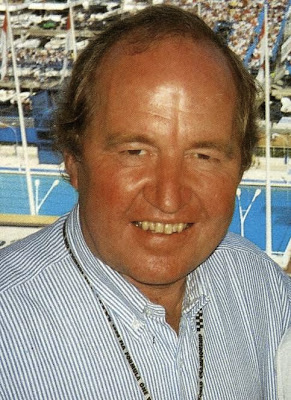

Yet none of them were quite a match for the best news-gatherer the sport ever had. Ill-health has consigned Eoin Young to a hospice in his native New Zealand but his From The Grid column in Autocar was obligatory for anybody in the business or out of it. Well-connected ever since he came to Europe and worked with Bruce McLaren in 1961 Eoin had the biggest scoops. His was the best-informed commentary, nobody knew as much as he, nobody spilled as many secrets and above all his writing told readers he was the insider’s insider. It didn’t matter if you were an outsider, Eoin had a way of gaining your confidence.

Eoin Young knew who was going to drive for whom next year – sometimes before they did. He knew who was up-and-coming and who was going down-and-out. He would take notes and print it yet I don’t suppose he ever broke a single confidence. If you told Eoin anything he would take it that you were, in effect, telling the world. He was only the means to the printed page. His veracity seemed to encourage his informants, who told him things they’d confide to no-one else.

Maybe a little rancorous in later years - his personal life was turbulent – Eoin was competitive and neither gave nor expected anything less than determined bargaining in books. His Autocar columns will be a priceless resource to motor racing historians, his books perhaps less so. They were variable; he seemed to grow bored with research or writing at length or in depth. His forensic skills were best in his brief, punchy impertinent style.