Well, maybe. That's what Camille Jenatzy (right) thought in 1899.

Behind FEH is London-based entrepreneur Enrique Bañuelos, CEO and shareholder is former MEP and racing team owner Alejandro Agag. Also associated are Lord Drayson, Labour’s old Minister for Science, and Eric Barbaroux, Chairman of the French electric automotive company "Electric Formula". Demonstrations of Formula E cars start next year, followed by a championship in 2014 with an objective of 10 teams and 20 drivers. The races "will be ideally" staged in the heart of the world’s leading cities, around their main landmarks. Well, maybe.

With luminaries like Drayson and an ex MEP involved, they'll be looking for subsidies from greenies. Paying customers would never make an electric grand prix commercial, yet expect FEH to be awash with taxpayer cash. And expect more announcements like: FOUNDATION OF SPARK RACING TECHNOLOGY. OFFICIAL SUPPLIER OF THE FIA FORMULA E CHAMPONSHIP. PARIS, 12th November 2012: Frédéric Vasseur is pleased to announce the birth of Spark Racing Technology, a company dedicated to the creation and assembly of cars participating in the FIA World Championship Formula E. E for electric, exciting, efficiency, environment, and last but not least, a new era. Well, maybe.

Spark Racing Technology will be part of a newly founded consortium whose purpose is to design the most efficient electric cars possible, in regard to mechanical, electrical, electronics and engine. Frédéric Vasseur is proud to announce that McLaren is among the key players in the said consortium. The collaboration of Spark Racing Technology with a major car manufacturer whose reputation and success speak for themselves is a guarantee of success and innovation. McLaren will provide the engine, transmission and electronics for the cars being assembled by Spark Racing Technology.

The FIA Formula E Championship will be launched in 2014.

The press release waxes lyrical. It will run exclusively in major international cities and it has all the assets needed to reach a worldwide audience, becoming a bridge between the old and new era of industry and motorsport. Frédéric Vasseur (CEO, Spark Racing Technology): “I am proud and happy to give birth to this project that is innovative and extremely rewarding for a company both technically and philosophically. Personally, I can write a new chapter, regardless of my other ventures in motorsport. Confidence and commitment from our partner McLaren is a guarantee of quality and reliability without which this project would not have been possible. The association with a globally recognized car manufacturer is definitely the right way to go. Sport and society are evolving and Spark Racing Technology is proud to be the pioneer and leader in the new field of electric cars that will revolutionize the motor racing industry and attitude.”

You can only hope that Martin Whitmarsh (Team principal, Vodafone McLaren Mercedes) had his tongue in his cheek: “I’m a passionate believer in the role that motorsport can play in showcasing and spearheading the development of future technologies, and regard the Formula E concept as an exciting innovation for global motorsport. McLaren has worked with Frédéric Vasseur for many years, and our association has been very successful. Working together in Formula E, McLaren’s world-class technology and Spark Racing Technology’s expert knowledge will combine to allow both companies to stay at the forefront of technical innovation and hopefully open up great opportunities for the racing cars of tomorrow.”

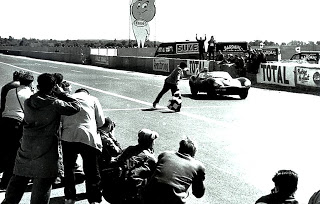

Or maybe not. Thought of a London Grand Prix in 1981 for Sunday Magazine