James’s Guild of Motoring Writers’ Driver of the Year Award seems to have taken place in a seedy night club full of girls, rather than the RAC in Pall Mall. He won the title twice and the film portrays the trophy as a little silver cup, which it isn’t. Scorning formal attire while the rest of us sat applauding in black ties, he made a witty speech. Demoting the occasion to a night club missed the point. By turning up at the RAC in open-necked shirt and plimsolls he was telling us someting.A real Guild Driver of the Year Trophy. Jim Clark's of 1963.

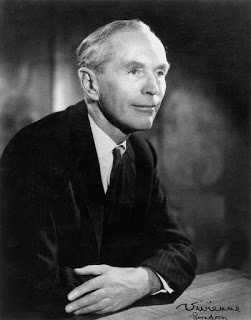

Still, the portrayals of James (Chris Hemsworth) (left above) and Niki (Daniel Brühl) are absolutely spot-on. Voices and mannerisms are completely authentic even if the script is careless. Alexander Hesketh’s sudden arrival and departure from Formula 1 was nothing like that, and the idea of “champers in the pits” as the extent of the team’s high living was nothing like that either. The most permissive censor would have blanched at the truth. Alexander was much noisier and heartier than his screen counterpart.

Louis Stanley was far more pompous and self-important, called everybody by surname. He even called Jackie “Stewart” in the ambulance after his accident at Spa. Yet the actor failed to catch “Big Lou’s” essential humanity. The film somehow misses Teddy Meyer’s excitement in Japan, holding his fingers up to tell a disbelieving James he was world champion.

However I can vouch for the veracity of James’s airliner experiences, portrayed graphically in the film. I sat with him in a Tristar on an overnight flight to the Middle East. Tristars had a tiny lift to the galley, with what was euphemistically referred to as a lounge area for off-duty stewardesses, below the passenger deck. At least twice (while I dozed I may say) James caught the lift. I never knew if it was two stewardesses or the same one twice. Or two at the same time.

Hard to believe Guy Richard Goronwy Edwards QGM is 70. After a glancing blow to Lauda’s crashing Ferrari, togther with Brett Lunger, Arturo Merzario and Harald Ertl, Guy stopped and went back to the burning car. In 1998 he told Autosport: “I could see him. I had time to run back and save him. It was very difficult. Petrol fires are awful and this was a big one. The heat and noise were incredible. I was running and thinking - do I really want to do this? The honest answer was No Way. But what could I do? Stop and walk back? The flames were so thick, I couldn't see the bastard. It was hot and there was choking dust everywhere. I knew it was now or never and with a desperate sense or urgency, and help from other drivers, feeling quite desperate, we were banging against each other, pulling, cursing and just struggling. His shoulder straps came away in my hands and it was incredibly frustrating, the heat was just so physical. I got hold of an arm and a good grip on his body and the little sod came out with all of us falling in a heap. We pulled him out like a cork from a bottle.”Niki’s worst burns were the result of catch fencing he had run into, knocking his helmet off. The track was blocked and the race restarted. Lunger’s and Ertl’s cars were too damaged to resume but Merzario and Edwards lined up on the depleted grid. Merzario lasted 3 laps, Edwards finished 15th in the old Hesketh, sponsored by Penthouse, painted up with a girl on the front. I was covering the race as a journalist and stayed up half the night writing Niki’s obituary.

Best line in the film? James to Niki: “You’re the only person I know who could get his face burned off and come out better looking.” Sums it up really.