Sochi was not the first grand prix overshadowed by conflict. The 1914 French Grand Prix took place six days after the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand. In 1938 Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz fled Donington as the Munich Crisis broke. German tanks rolled into Poland during practice for the Belgrade Grand Prix run on September 3rd 1939.

Putin’s grand prix has, for the moment, damped down Ukraine’s uncivil war in which 3,600 have already died. Or maybe it has kept a lid on it until Bernie’s circus moved on.

In July 1914 feelings in France were already running high when the home crowd cheered Peugeots and Delages against the might of Mércèdes. In a seven hour contest on a triangular course near Lyons Georges Boillot’s Peugeot was overwhelmed by Christian Lautenschlager’s Mércèdes. It was a triumph for the German team, which took the first three places.

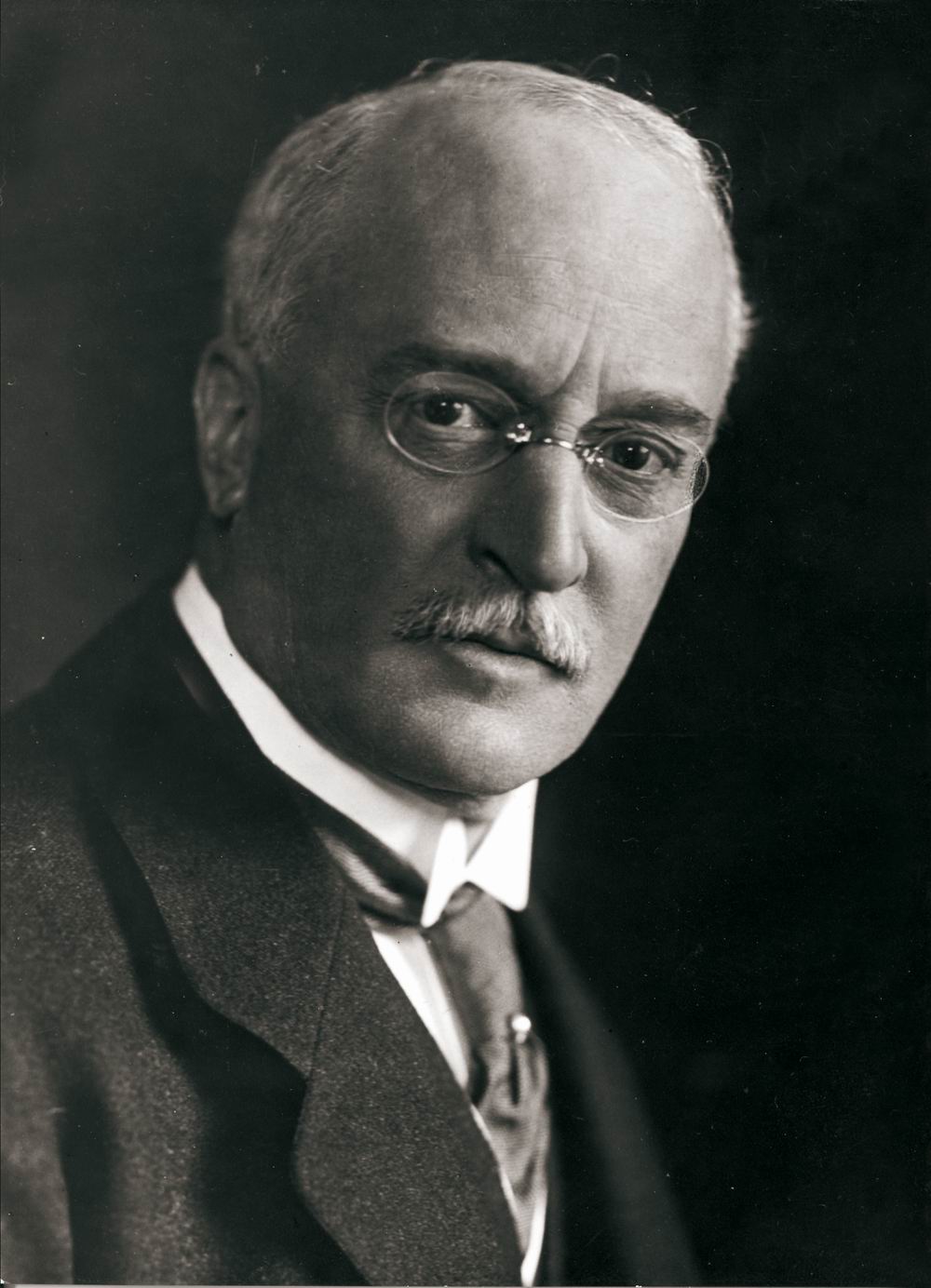

SCH Davis: “As the crowds made their way dustily from the course there was an atmosphere of something more than motor racing. Everyone was extraordinarily quiet. Though we knew nothing of it there had come faintly in the wind the echoing thud of guns.” The gallant Boillot became a casualty, shot down over the Western Front in 1916. Yet there was a curious bonus for Britain. One of the Mercédès, sent for exhibition in London, was somehow forgotten when the war began and came to the attention of a young Lieutenant WO Bentley RN. The former railway apprentice had the job of improving Royal Naval Air Service engines. He knew the Mercédès, designed by Paul Daimler, was derived from an aero engine with 4-valve heads, steel forged cylinders and a thin welded water jacket to reduce weight and improve cooling. Mércèdes attention to detail was exemplary. The rear axle had double pinions and crown wheels machined integrally with the half-shafts, hollowed-out to save weight. The axle was a masterpiece of precision.

Lieutenant Bentley towed the Mercédès to Rolls-Royce at Derby where they knew about aero engines. It was taken to pieces, its secrets examined and some were incorporated into Rolls-Royce’s engines. Bentley meanwhile redesigned RNAS Clerget air-cooled rotaries.

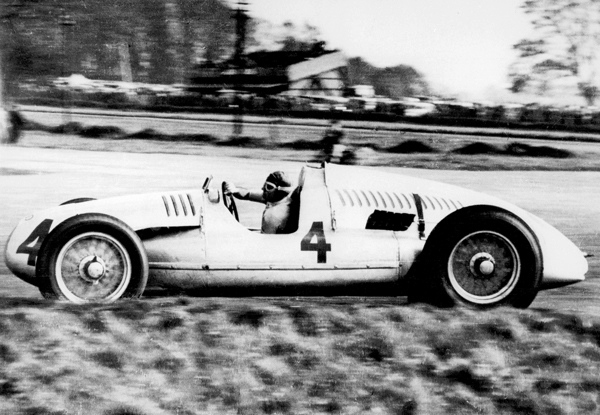

The 1938 Donington Grand Prix was planned for 1 October but on 24 September talks in Bad Godesburg between Hitler and Neville Chamberlain over the future of Europe collapsed. The Royal Navy was placed on alert, which meant that Francis Curzon 5th Earl Howe a serving officer withdrew his ERA entry. The German teams, however, were already there, nearby Castle Donington having served as a World War I prison for German officers. Karl Feuereissen, Auto Union manager and Alfred Neubauer his counterpart at Mercedes-Benz were instructed to return to Germany at once. And, mindful perhaps of what befell the 1914 Mercédès, if there was any threat of confiscation the racing cars had to be set on fire and destroyed.

As it turned out they caught the ferry at Harwich intact, only returning after Neville Chamberlain waved his famous piece of paper on September 30. The race was re-scheduled for October and German cars took the first five places.