Royce and Lanchester were good at suppressing vibrations. Edwardian heavyweights had a cloistered calm difficult to reproduce in modern resonating light weight saloons. Cars now make so many noises, tyre and wind roar, gear whine, body drumming it’s difficult to know where to start. It’s not just vibrations, which Royce and Lanchester believed were better eliminated at source. Engines make all kinds of racket, pistons slap, valvegear rattles, exhausts boom, turbos wail and drive belts howl. Sub-frames and absorbent bearing materials made a difference but for years it was mostly down to filling cavities with felt or polystyrene.

Silver Ghost, epitome of quietness

Ford’s Active Noise Control (ANC) now cancels noises out by playing them back at you. They say it’s like noise-cancelling headphones to occupants of its Mondeo Vignale.

Nothing’s new. Twenty-five years ago I went to Hethel for a demonstration of what Lotus was calling Adaptive Noise Control. It worked much the same way.

Sunday Times 4 February 1990.

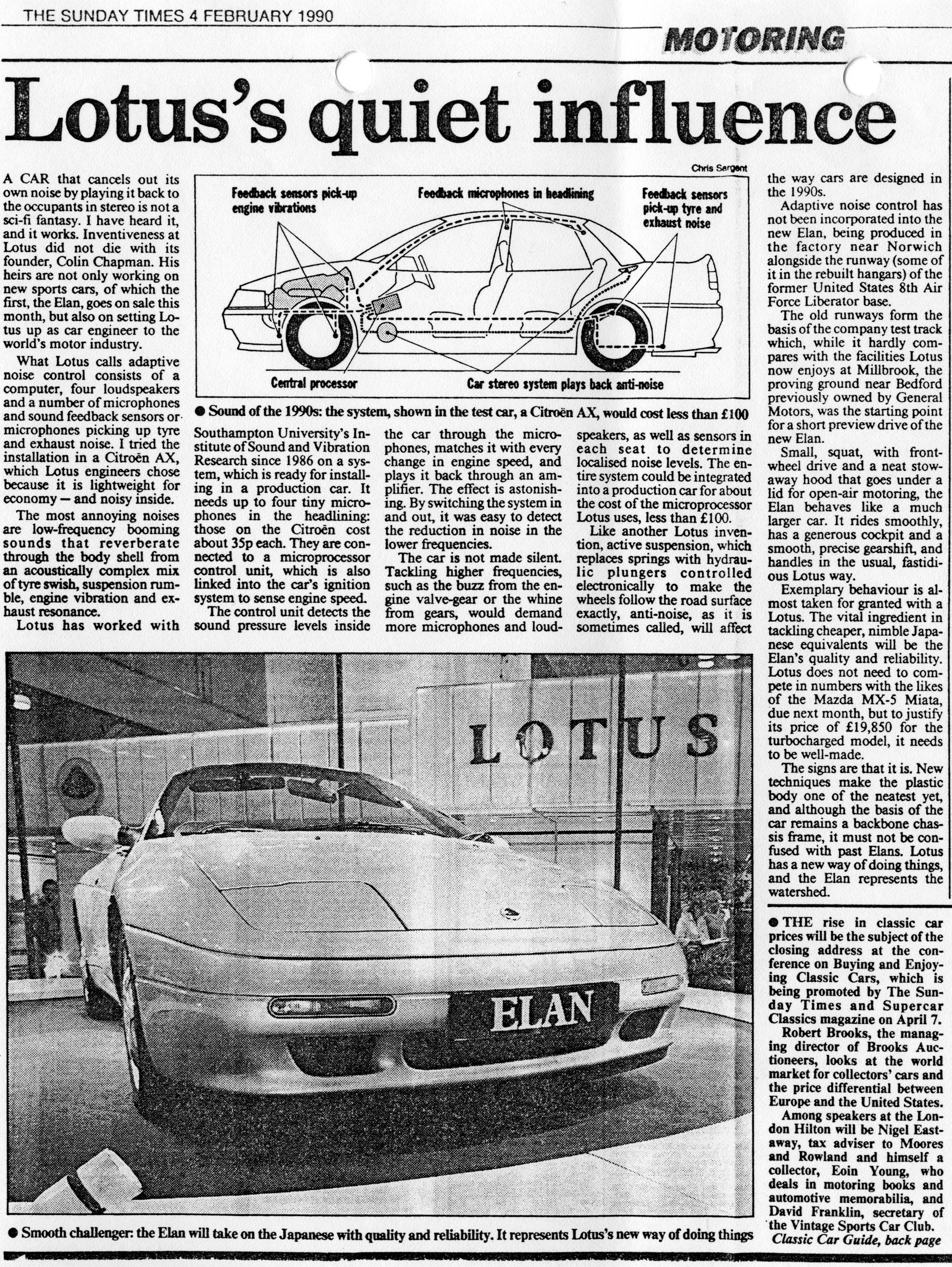

A car that cancels out its own noise by playing it back in stereo is not a sci-fi fantasy. I have heard it, and it works. Inventiveness at Lotus did not die with its founder, Colin Chapman. His heirs are not only working on new sports cars but also on setting Lotus up as engineers to the world's motor industry.

What Lotus calls Adaptive Noise Control consists of a computer, four loudspeakers, a number of microphones and sound feedback sensors picking up tyre and exhaust noise. I tried the installation in a Citroën AX, which Lotus engineers chose because it was made light in weight for economy.

Lightweight cars tend to be noisy inside and adding layers of heavy sound-damping materials could cancel out the savings. The most annoying noises are low-frequency booming sounds that reverberate through the body shell from an acoustically complex mix of tyre swish, suspension rumble, engine vibration, and exhaust resonance.

Lotus has worked with Southampton University's Institute of Sound and Vibration Research since 1986 on a system, which is now ready for installing in a production car. It needs up to four tiny microphones in the headlining, those on the Citroën, Lotus engineers pointed out to me with some satisfaction, cost about 35p each. They are connected to a microprocessor control unit which is also linked into the car's ignition system to sense engine speed.

The control unit detects the sound pressure levels inside the car through the microphones, matches it with every change in engine speed, and plays it back through an amplifier with 40 Watts RMS per channel. The effect is astonishing. By switching the system in and out, it was easy to hear the reduction in noise by up to 20 dB in the lower-frequency sounds below about 100HZ.

The car is not silent. Tackling higher frequencies, the sort of buzz that comes from the engine valvegear, or whine from gears would demand more microphones and loudspeakers, as well as sensors in each seat to determine localised noise levels. In production examples, the system could be incorporated into a car's stereo system relatively cheaply. The entire system could be integrated into a production car for about the cost of the microprocessor Lotus uses, which is less than £100.

The implications of anti-noise as it is sometimes known, go beyond introducing Lotus-licensed setups in production cars. Like another Lotus invention Active Suspension, which replaces springs with hydraulic plungers electronically controlled to make the wheels follow the road surface exactly, it will affect the way cars of the 1990s are designed. It makes softer engine mountings practical, which would not only mean quieter cars, but also make them almost vibrationless.

Ford’s Active Noise Control developed in its semi-anechoic chamber (above) is to be offered on other vehicles, including the Ford Edge coming in 2016. Engineers from Sony tuned the Vignale audio system for what it calls an exceptional acoustical experience with a customised stereo mode, a true surround experience. It has three microphones strategically placed to detect undesirable noises, counteracting them with opposing sound waves from the audio system. It doesn’t affect, they say, volume levels of music and conversation. Driver and vehicle behaviour is anticipated, for example when accelerating in a lower gear.

“Whether listening to a favourite playlist, tuning into a much-loved station, or simply enjoying a respite from the demands of modern life, the experience of sound – and just as importantly silence – can be a fundamental part of an enjoyable car journey,” according to Dr Ralf Heinrichs, supervisor, Noise Vibration Harshness, Ford of Europe, “Active Noise Control offers drivers enhanced levels of comfort, and fewer distractions.”

The Mondeo Vignale also has acoustic glass (above) to quieten air eddies round the windscreen. A layer of acoustic film reduces noise around the A-pillars. The Dunton test track has noise-inducing gravel and potholes. Engine bay insulation in the Mondeo Vignale is foam rather than fibreglass and reduces powertrain noise in the cabin by up to 2 dB.

Sound‑proofing in the underbody shield, wheel arch liners and doors block tyre noise, and the integral link rear suspension also contributes to reduction by 3 dB. Sound engineers from Sony Corporation tuned the Vignale audio system for, “an exceptional acoustical experience on the road with a customised stereo mode, and a true surround experience.” The Ford factory in Valencia where Mondeos are made (Vignales are hand-finished at a Vignale Centre) has a 300m ‘rattle and squeak’ circuit to help engineers ensure everything sounds right. Another test reflects increasing use of audio via Bluetooth from external devices like smartphones.

1922 OD Vauxhall - on a calm evening.