Understatement never did much for Henry O’Neal de Hane Segrave. First British driver to win a Grand Prix and seven more major races, three land speed records, German and European speedboat championships and the water speed record. Next March marks 90 years since he did 231.44mph at Daytona with Golden Arrow. He even had a car named after him but, modest to a fault, he is now remembered through a JD Wetherspoon’s pub in Southport and an RAC Trophy.

Sir Henry Segrave could have been a GA Henty hero or a prototype wartime Biggles had he not been shot down so often. “I was a rotten pilot. It wasn’t so bad once I was up, but I always seemed to make a mess of landing.” Generous to opponents; he wrote from the Western Front, “By jove, the German snipers are A1 shots. They have a special rifle with telescopic sights. I put a biscuit up on a split stick, and there were two shots at once, one of which bust the biscuit.” His father felt “awfully bucked” when Second Lieutenant Segrave’s corporal gave a good account of his keenness and bravery.

He did not get through unscathed. A bullet in the wrist at the second battle of Ypres then, a few days later, after “a deuce of a time getting back from the German lines a chap shot me from about four yards off. He came for me with a bayonet: my revolver was clogged with mud, jammed and useless. All I had was a machine gun and ammunition belt, which I threw at him as hard as I could. It got him in the chest and stopped him. And then he put up his rifle and pulled the trigger. I just ducked in time and the bullet went through my left shoulder and passed out at the bottom of the shoulder blade.”

He survived to take up flying but was shot down in a DH2. He went on to a single-seater FE8 scout, only to be caught once again by anti-aircraft fire at 7,000ft, crashing a second time and suffering a badly broken ankle. Stirring stuff. The wounded hero returned to London and married a glamorous actress; you would never write a script like this. It is too valiant for words.

The Sir Henry Segrave pub, 93-97 Lord Street, Southport PR8 1RH, commemorates his 152.33mph on Birkdale Sands in March 1926. Speed record attempts were usually at Pendine but Birkdale, across from Lytham St Annes, was nearer Sunbeam’s works at Wolverhampton. Louis Coatalen may not have been convinced two 2 litre 6-cylinder engines on a common crankcase making a 75deg V12 worth a journey to South Wales. Land Speed Records were made with 18 and 22 litre monsters, so implausible for a 4 litre with fragile supercharging.

Serving in 1918 with the British Aviation Mission to New York, Segrave watched Ralph de Palma racing a 12-cylinder Packard. At 110mph it was as fast as Segrave’s aircraft, so he took his 60bhp Apperson touring car on the two-mile board speedway track at Sheepshead Bay, Long Island. He enjoyed it and got a plaque verifying a lap at 82mph.

Returning to Britain, he took up motor racing as a substitute for flying and drove works Opels, left over from 1914, at Brooklands. Racing cars as booty were not a novelty in either war although Segrave claimed he obtained them honestly. By 1921 he had worked his way into a works team for the French Grand Prix and while Sunbeam-Talbot-Darracq paid the entrance fee he had to meet his own expenses and pay for any damage to the car.

It was not an auspicious debut. The cars were badly prepared, uncompetitive, and withdrawn on the eve of the race. Segrave pleaded to be reinstated, finishing ninth and last, yet in 1923 gained his historic victory in the French Grand Prix at Tours in the 2 litre Sunbeam. Like Ferrari, Senna, Bugatti and Porsche he gave his name to a car, fittingly however it was nothing extravagant. The 1928 Hillman Fourteen “Segrave” was a Weymann fabric coupe with white wire wheels at £398 guaranteed for 60mph.

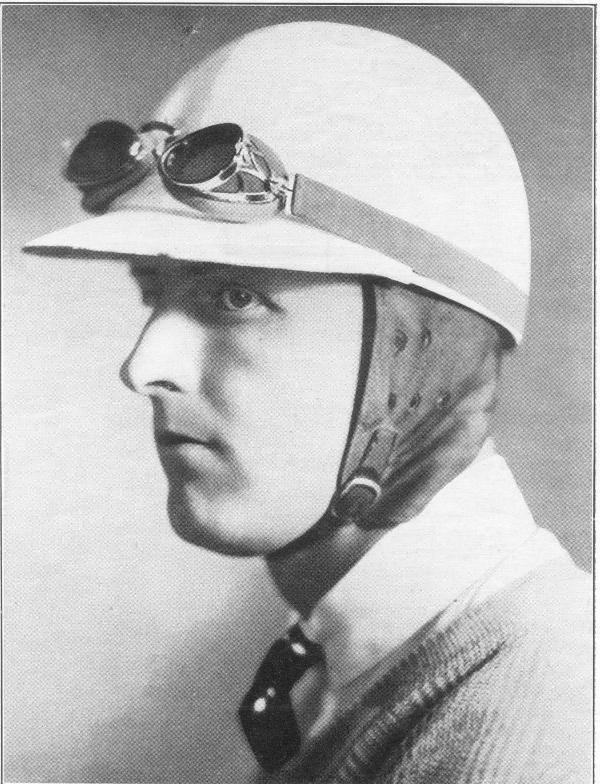

In 1927 Major Segrave was first to break 200mph in the “100HP” Sunbeam. Two V12 twin ohc 22.5litre Matabele aero-engines gave a total of 870bhp @ 2000rpm. Photographed at National Motor Museum, Beaulieu. Heading picture at Daytona.

Following the 1926 exploit remembered by Wetherspoons, a year later he took the 44.8 litre twin-engined “1000 horsepower” (it never was) Sunbeam across the Atlantic to Daytona Beach and did 203.79mph. He was faster still in Golden Arrow, which cost £11,559 15s 4d to build at KLG’s Putney Vale works where Segrave was competitions manager. Designed by JS Irving its bodywork was wrapped closely round a 930bhp Napier Lion engine from the 1927 Schneider Trophy seaplane, in a pioneering essay of aerodynamic ingenuity. Irving even built in downforce, reinvented for Formula 1 in the 1960s, which kept Golden Arrow flying close to the flat sand of Daytona Beach for the sake, as Segrave put it, of the driver’s peace of mind.

Beaulieu exhibit of Golden Arrow showing how the bodywork wrapped tightly round the three banks of cylinders in the Napier Lion engine. Alongside the “1000” HP Sunbeam.

Golden Arrow only ever did some 50 miles on its wheels before the engine’s three banks of cylinders were filled with oil, presumably Castrol since CC Wakefield put up the money, and it was made over in due course to the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu. A good deal of it had gone missing. The clutch and driveshafts were probably disconnected, enabling it to be moved on exhibition and the fragile surface radiators were gone.

Segrave began life in Baltimore, USA on September 22, 1896, settled in Kiltymon, Co Wicklow and it is time he was rehabilitated in our national pantheon alongside the Campbells pere et fils, Eyston, Cobb and Goldie Gardner. He died an idol on Friday, June 13, 1930, on Lake Windermere where his riding engineer in Miss England II, Michael Wilcocks thought he tried to keep control of the boat even after her mahogany bottom was torn out by floating debris. “I definitely know Sir Henry stayed in and went over with her, thereby receiving his terrible injuries. He realised that the only thing to do was to keep power on so that the slipstream from the propeller on to the rudder would enable him to steer, slow down, and give us a chance.”

Segrave was taken out of the water conscious asking: “How are the lads? Did we break the record?”

The Royal Automobile Club awards the Segrave Trophy for outstanding skill, courage and initiative on land, sea or in the air. It went first to Air Commodore Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith for long-distance flights and Amy Johnson (1932), Bruce McLaren (1969), Sir Jackie Stewart (1973 and 1999) and Sir Frank Williams (1992). Nine motorcyclists won it including John Surtees, Barry Sheene, Joey Dunlop and Geoff Duke. Jet pilot Neville Duke and Stirling Moss gained it and on 1 May 2018 it went to another motorcycle racer Sam Sunderland. “For being the first Briton to win a Dakar Rally crown, winning the motorcycle category in 2017’.

RAC Chairman Tom Purves (left) awards the Segrave Trophy of 2015.