I’ve written a million words on Jaguar. 120,000 in each edition of The Jaguar File, three or four re-writes and up-dates of its digital equivalent, road tests and features over sixty years. So, a Jaguar expert? Maybe not. Driving an F-type last weekend I had to admit I have to look up my own books for things. More a Jaguar student than a know-all.

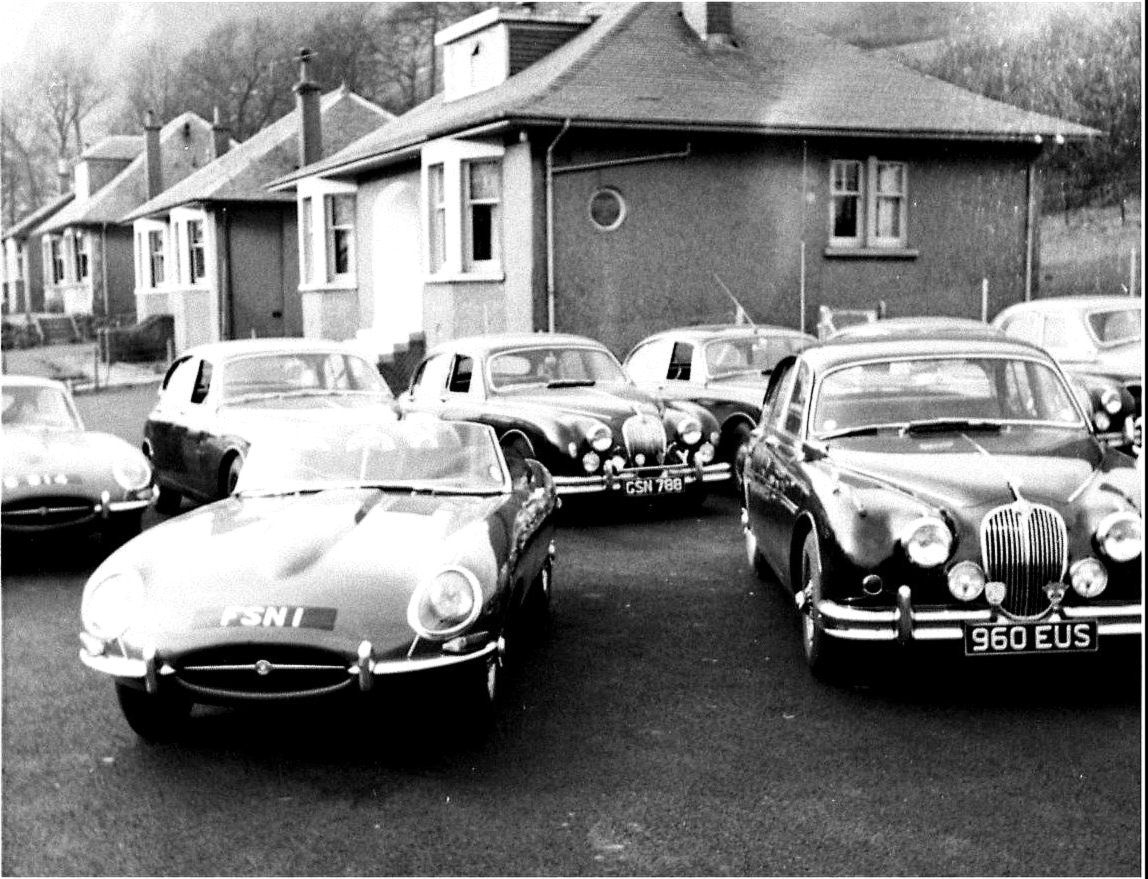

I was driving Jaguars years before I took picture top left in 1961 or maybe 1962. It is Stewart’s of Dumbuck’s E-type FSN1 with which Jackie started racing. Next right is the F-type on the same spot last week when we drove over from Mar Hall where the Association of Scottish Motoring Writers was presenting Ian Scott Watson with the Jim Clark Memorial Award. Jaguar was sponsoring it in view of Jim’s exploits with the Border Reivers’ D-type. Ian largely organised in the early years.Jim’s road-going 3.8 with its BRDC badge is alongside FSN1 and the E-type behind is Ronnie Morrison’s.

The red E-type is FSN1 again at Trump’s Turnberry. I drove it lots together with Jackie’s older brother Jim, who won so much with Ecurie Ecosse that Lofty England wanted him to partner Mike Hawthorn at Le Mans in 1955. Just as well maybe, in view of the huge accident, that he didn’t. Jim overturned an Ecosse D-type at the Nürburgring and largely at their mother’s behest retired from racing and turned the offer down. We took FSN1 to Turnberry for the Royal Scottish Automobile Club Concours, which explains the white sidewall tyres.

Jackie (top right) worked on the forecourt of Dumbuck, which sold Jaguars to the rich and famous round Dumbartonshire. Jackie’s plaque (below left) adorns the family home beside the garage. Last week the former Stewart family house was undergoing refurbishment and when I was taking the picture the family moving in asked if I could identify old photographs they’d found. One was of Bob Stewart, Jackie and Jim’s pipe-smoking father who put me on to a special mixture blended for him by Rattray of Perth. Another was a cracked and crinkly print of Jim in his first Healey Silverstone. Dumbuck Garage, Milton is now a Vauxhall dealer and Managing Director Damon Lindsay AMIMI kindly moved some of his stock of Vauxhalls to make way for the F-type.

Ian Scott Watson in the middle (above) put Jim Clark on track for the first time 62 years ago this weekend. Together they had driven from the Borders to Crimond, Aberdeenshire, far enough they hoped from the Clark family’s disapproval. Jim had taken on responsibility for farms and they didn’t want him starting something that would mean him taking time off. The racing car was Ian’s DKW Sonderklasse, 3 cylinder 2-stroke, front wheel drive a bit like an early Saab and Ian set Jim up as reserve driver. Unsurprisingly he was 3 seconds a lap quicker than Ian, whom the organisers thought was sandbagging to get a better handicap.

Without Ian’s encouragement Jim Clark might never have been persuaded to be a racing driver. It was not until David Murray paired him in the Ecurie Ecosse Lister-Jaguar at Goodwood in 1959 that he could be convinced. When he realised he was every bit as fast as Gregory, Clark knew he was world class. John Murdoch, president ASMW is on the left and and Ken McConomy Head of Jaguar Land Rover PR on right.

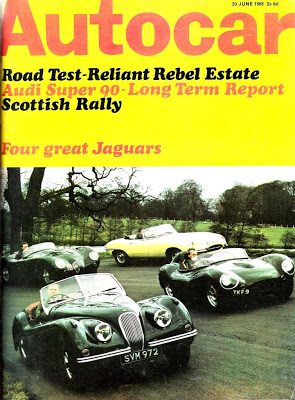

I drove TKF9 (above), Clark’s old Border Reivers’ D-type at Oulton Park in 1968 for an Autocar track test of XK120, C-type, D-type and E-type. “Climb into the D-type through a tiny fragile door. It’s like a space capsule. Close fitting, fully instrumented, functional. The leather is soft and the seat hugs you. The view over the front is like a bulgy E-type. Superficially it does feel like an E-type; smooth ride, the easy way you can power out of corners yet keep a firm grip of the track. Everything is direct. The steering is sensitive, cornering progressive and predictable. With the good manners of Dunlop racing tyres and the car’s splendid balance you can break it away at the front or the back or on all four wheels at once if you want. The D-type does as you tell it to. No more, no less.” There was no forgetting that it had once been handled by the world’s best racing driver although it was better on fast circuits than in tight slow corners.

A decent F-type (below left) with well over 125 bhp more than Jim’s early-model D-type could easily outpace it. Even with space for two and luggage, air con, sat-nav and a fancy roof that goes up and down by itself it is all you would expect of a modern space capsule. We didn’t rush a lot between Mar Hall and Dumbuck but it handles peaceably and almost unobtrusively. It is just as much Jaguar brand as the E-type was all those years ago.

D-type MWS 302 (chassis XKD502) never had the luck of its near-identical twin XKD501 registered by Ecurie Ecosse, Edinburgh as MWS 301, which was the Le Mans winner sold by Sotheby’s for a record £16.6million two years ago. By the time I drove 302 to Le Mans in 1966 it had fallen on hard times. The Automobile Club de l’Ouest wanted to parade past winners of the 24 hours’ race and it still looked much like 301, so its then owner Michael McGrath and I drove it all the way there. It was not a dry run. D-types had no hood. This is me (below right) taking it through Mulsanne.

ASMW Press Release. Saturday 9 June 2018

Sixty-two years almost to the day after launching the career of Scotland’s greatest racing driver, Ian Scott Watson (born 1930) has been recognised by the Association of Scottish Motoring Writers (ASMW). At a ceremony in Mar Hall recalling Clark’s early exploits with a D-type Jaguar, he was presented with the Association’s annual Jim Clark Memorial Award which, “Acknowledges and rewards the outstanding contribution of a Scot or Scots for services to motoring.”

Jim Clark was launched on his way to two world championships and a record series of Grand Prix victories at Crimond, Aberdeenshire on 26 June 1956. Convinced of his friend’s talent Scott Watson persuaded him to take part in a race run by the Aberdeen and District Motor Club. Their 250mile drive from the Borders to the windswept disused airfield eight miles from Fraserborough took five hours. There was no Forth road bridge or motorway in 1956.

Scott Watson thought the DKW a likely winner in Scottish rallies against Renault 760s, Standard 10s, Morris Minors, and Austin A30s. The “Sonderklasse” with a 3-cylinder 2-stroke engine and front wheel drive was an eccentric choice for sprints, and gymkhanas. At Crimond Clark was 3 seconds a lap quicker than the owner in practice and the organisers suspected Scott Watson of driving slowly to get a better handicap in the saloon race..

Clark took a lot of motivating. He did not realise how good he was. Scott Watson spent years, providing him with expensive cars including a Porsche and a Lotus Elite: “I may not have been a judge of what was required to make a grand prix driver, but I could tell from the way Jimmy drove both on the road and on the track that he was exceptionally quick. On the road he was amazing, perfect to sit beside. His driving was smooth, his anticipation marvellous. You could feel him ease off the throttle and then spot a car he had already seen approach on a distant side road. It was difficult to know why he did not feel confident about his own ability. He chewed his fingernails even then. He lacked confidence, yet when he got on the track it was totally forgotten. He gave it everything and drove superbly.”

Scott Watson’s motives were altruistic. He loved motor racing and once Clark’s ability emerged saw himself in the role of promoter. He was first to provide a car, took every initiative in advancing Clark’s career and effectively organised his exploits with the Border Reivers’ D-type Jaguar. His first race at Full Sutton earned a place in the record books as the first sports car driver to lap a British circuit at over 100mph.

Yet it was not plain sailing. Having accompanied Clark, in effect running his business affairs when he was taken on as a Grand Prix driver by Lotus, Scott Watson was asked to take a back seat. He wrote later that being forbidden to act as Jim’s manager was a blow. “I thought I might have had a small managerial percentage of his winnings and recoup some of my large personal outlay. Later Jim did leave me a small bequest in his will, which I appreciated.”

Sir Jackie Stewart describes Clark as, “… the best driver I ever raced with and against”. Three times Le Mans winner Allan McNish: “A modern driver winning the British Grand Prix, racing in Formula 2, then at Indianapolis would be unthinkable.” David Coulthard: “Jim’s achievements and Jackie Stewart’s input were fundamental to me becoming a professional racing driver.” Dario Franchitti: “He was my hero”. The four patrons of the Jim Clark Trust wrote Forewords to the new edition of Eric Dymock’s life of Jim Clark. Updated and redesigned, it celebrates the life and achievements of Jim Clark (1936-1968) and a royalty on every copy goes to the Jim Clark Trust.

Jim Clark rewrote the annals of American racing at Indianapolis, second at his first attempt in 1963, winning in 1965. He narrowly missed four consecutive world titles. Misfortune in the closing laps of the final race of the season twice denied him a unique quartet. Some of his other records remain secure however. His eight “grand slams” (pole position, leading every lap, fastest lap and winning a Grand Prix – his closest rivals Alberto Ascari and Michael Schumacher managed only five) is unlikely to be broken. He seemed a match for any odds during eight dangerous years at the top of motor racing, yet died in an unlikely accident at a minor event at Hockenheim on April 7 1968. Genius at the wheel was not enough. Rivals’ subsequent safety campaigns saved countless lives on and off the track.