Report Eric Dymock, Illustration Geoff Hunt: Sunday Magazine 11 October 1981

A full-scale British Grand Prix sweeping through Parliament Square with Big Ben showing a new lap record is very much a piece of artist Geoff Hunt’s imagination. But racing cars tearing along Park Lane at 180mph, braking hard into the sharp right-hander by the Hilton Hotel, and going flat out in fifth gear past the Serpentine—that’s all very possible and long overdue, according to Innes Ireland, robust veteran of 50 world championship races

Today, the final round of the 1981 Grand Prix circus is being staged in the car park of a Las Vegas hotel. In recent years Long Beach, California, has established its own Monte Carlo- style round-the-houses race, as has Montreal, and next year Detroit will follow suit.

"So why not a Hyde Park Grand Prix?" asks Innes Ireland. "It would be amazingly enter-taining for the crowds and great stuff for the drivers. "Look at the crowds they get in Montreal. They come by public transport, so there's no parking in a muddy field till after dark. So long as pits and crowd safety are right it would be a marvellous spectacle. You would be bringing motor racing to the people, not the other way round."

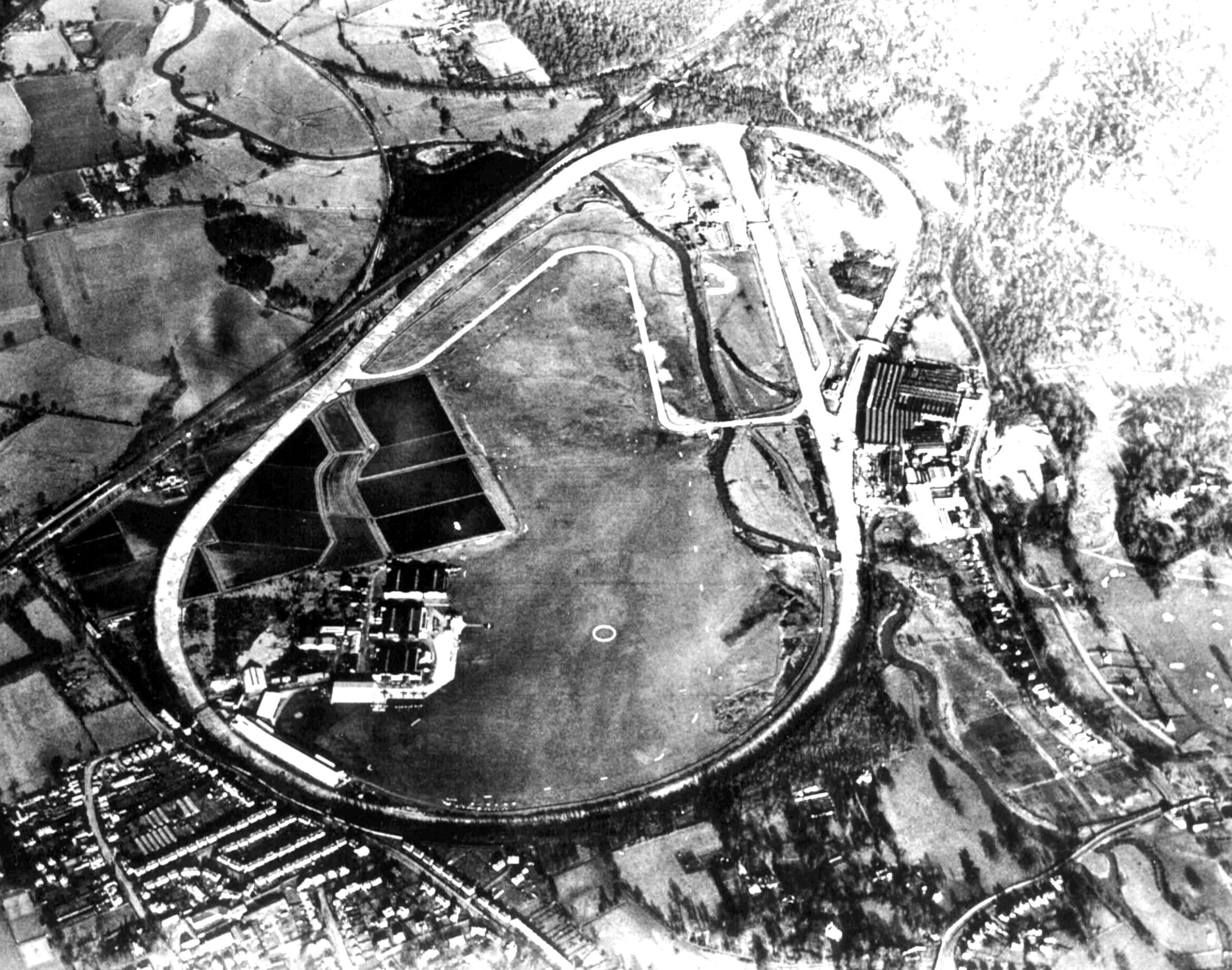

ABOVE: Innes Ireland leads Jo Bonnier at Silverstone. Goodwood 1960s, Denny Hulme (Brabham Honda F2)) interviewed on the starting grid by Basil Cardew of the Daily Express and David Phipps. 1967 Monaco, where you could cover the Grand Prix closely from the sidewalk. Brooklands classic programme.

It's an idea that contradicts the whole concept of purpose-built autodromes, an example of which is the gleaming concrete Circuit Paul Ricard in the South of France. It was built by the aperitif millionaire as a safety-first super-circuit with wide spin-off areas, and carefully graded bends between its glistening white kerbs. But the racing cars are separated from the spectators by as much as a hundred yards. The wide safety zones make the cars remote and tend to diminish the sense of speed for the spectators. In Las Vegas the crowds will be close enough to smell the rubber-smoke as the tyres fight for grip, just a few feet beyond the crash barriers.

Surprisingly, while it’s true that the chance of an accident remains, its consequences tend to be less serious. For all the proximity to walls and kerbs, and the absence of spin-off zones, Monte Carlo's safety record since 1929 has been well-nigh perfect.

The very first motor racing took place on roads running from town to town - not on formally laid-out circuits. Around the turn of the century, it was almost exclusively a French sport, with races running from Paris to Amsterdam. Paris to Berlin. Paris to Innsbruck. But it came to an end in 1903 with the ill-starred Paris-Madrid race in which a number of fatal accidents occurred.

For subsequent contests in Europe roads were closed off. and races were run on loops forming a circuit in and around towns, with the competitors covering as many laps as they could. In Britain, opposition to cars in general, and closure of the King's Highway in particular, proved a handicap. There was also a national 20 mph speed limit.

In 1906, eminent Victorian builder Hugh Fortescue Locke-King built the Brooklands Motor Course near Weybridge in Surrey - a gigantic concrete saucer. With no precedent, it was built along the lines of a horse race course, it had a finishing straight, the drivers wore jockeys' silks not numbers, and the programme was called a Race Card. There was on-course betting and the races tended to be called things like The Household Brigade Handicap and Gottlieb Daimler Memorial Plate.

While throughout the rest of the motor racing world road racing was flourishing, in Britain it was not only discouraged but, officially, banned. This happened as the result of a mishap on March 28, 1925, at a hill-climb meeting run by the Essex Motor Club at Kop Hill in Buckinghamshire when a Bugatti injured a spectator..The closure of public roads for the purposes of competitive driving was from then on forbidden on mainland Britain.

It continued, however, to flourish in Europe. A motor race was a tourist attraction from Albi in France to Zbraslav Jiloviste near Prague. The Grand Prix became as much a feature of Monte Carlo as the Casino. An 8½-mile circuit, which included the main road to Tours, transformed Le Mans from being a place of historic interest (the Medieval tomb of the Angevin kings) to a household name in the modern world.

The only authorities within United Kingdom jurisdiction which could, by virtue of their measure of independence, close roads for racing were in the Isle of Man, the Channel Islands and Northern Ireland. The longest was the 52-mile Isle of Man course which had been used for the 1904 Gordon Bennett Trophy, and later the Tourist Trophy. To reduce disruption to traffic, the course was reduced to 40 miles in 1906. The 1928-36 Tourist Trophies were run in Northern Ireland on the Ards circuit, comprising a 13.6mile triangle east of Belfast from Dundonald-Newtonards-Comber, including an S-bend in the village itself. However, an

accident in 1936 in which eight spectators were killed at Newtonards closed the course.

After the Second World War the 7.42-mile Dundrod circuit in Northern Ireland was used instead. Five races were run here, of which three were won by Stirling Moss. (But his final victory in 1955 for Mercedes-Benz was marred by a multiple fatal accident and Dundrod was never used again.) British enthusiasts had watched enviously as motor racing in Europe got under way again after the War. The French ran one. within a few weeks of the Liberation, in the Bois de Boulogne (the Hyde Park of Paris); the British remained confined to the Manx Cup and the Castletown Trophy, or the Junior Car Club's Jersey Road Races at St Helier.

The army retained use of the pre-war road circuit on private ground at Castle Donington in the Midlands. The Brooklands motor course in Surrey remained an airfield. There was no alternative but to find new sites, and a number of war-time aerodromes were pressed into service. Goodwood, the old Battle of Britain station at Westhampnett. became one of the first. The former Bomber Command airfield at Silverstone saw its first race in 1949. Yet these were never regarded as anything but stop-gaps until racing could be organised on real roads.

The best of several schemes for a London Grand Prix came in 1948. when the British Racing Drivers' Club proposed a course that would run round Hyde Park and take in a section of Park Lane. Lord Howe, who was Chairman of the BRDC, a former racing driver and Tory MP. prepared, with the club's secretary Desmond Scanned, an Act of Parliament to make it legal.

They even obtained formal permission from George VI to use the park. The traffic islands they used at the time were moveable, (as they still are in The Mall for processions), and there was considerable support from trade and industry for a project that could be expected to boost exports. But the Metropolitan Police, who were apprehensive about large crowds and the problems of car parking, put up strong opposition to the plan. Richmond Park was put up as an alternative but was also unsuccessful in getting through Parliament.

Edinburgh's Holyrood Park, the Glasgow site of the 1938 Empire Exhibition and Cardiff city centre have all figured in similar proposals over the years None of these ideas came to anything. They all fell at the hurdle of the Parliamentary Bill which would be required to exempt competitors from being subject to the statutory speed limit—even if the local authorities could be persuaded to close the necessary roads.

The idea of racing in town streets grew cold in the Sixties with the call for circuits to be made safer. Drivers were horrified at the idea of racing close to walls, lamp-posts and kerbstones. The 1955 Le Mans disaster, when Pierre Levegh's Mercedes-Benz disintegrated in the crowd, killing 83. was fixed immovably in the mind of every race promoter. Nearly all the street circuits fell into disuse; new tracks came in. and others were modernised to new safety standards. Yet Monte Carlo carried on. Its record of only one fatal accident during a Grand Prix since 1929 held the key. Long Beach similarly set up its track in and around the town. Now Las Vegas has created its own street circuit—in the car park at Caesar's Palace, which was set up to look like streets.

And still Britain falters. The precious Act of Parliament, in which proposals were made to allow motor-racing in Birmingham, put up in 1973. contained so many other controversial city issues that it was turned down in its entirety. Yet crowds of 200.000 turned up to the 1980 Motor Show publicity parade of racing cars round the Bullring. The promoter, local businessman Martin Hone, says the roads were clear within 20 minutes of the event—which would seem to dispose of any objections on account of crowds and parking problems.

But still the city stalls at running a proper race. Ironically Hone's promotional efforts are so successful that the Arabs have quickly collared him to organise a Dubai Grand Prix in December, for which the authorities are building an extra 1.6 kilometre of street. But racing in British streets still awaits the green light.

ABOVE: 1908 Brooklands was shaped by horse-racing. 1981 pioneer Martin Hone explains his plans in Dubai. Extra track was built (view from my room in the Hyatt Regency).