Inseparable as Gilbert and Sullivan or Victoria and Albert, Rolls and Royce created the world's most recognisable brand name 110 years ago, Wednesday 4 May 1904. They met at the Midland Hotel Manchester not only producing “The Best Car in the World” (Rolls-Royce was never modest), but aero-engine excellence throughout the Second World War and ever since.

Right: Merlin in a Spitfire.

Only a little of the credit belonged to The Hon Charles Stewart Rolls,

(below)

an Edwardian gentleman to his elegant fingertips, complete with uniformed chauffeur and mechanic, but famously stingy. The late Sir Thomas Sopwith described him as, “curiously unlovable.” Rolls felt he had little to learn from Royce, a northern engineer, a crane manufacturer with an infinite capacity for taking pains. But as an ardent balloonist and aerial adventurer Rolls’s lifestyle was expensive, and the sales company set up with £6,500 from his father, Lord Llangattock, needed a new line to augment his imported French cars. Flying exploits were his undoing. Rolls achieved the melancholy distinction of being the first pilot killed in a British air crash at Bournemouth on 2 June 1910.

Workaholic, obsessive, sickly Frederick Henry Royce’s pursuit of perfection knew no bounds and, ill from overwork, he dismantled his Decauville to make it function properly. It was a car, he concluded, “...marred by careless workmanship,” so he set about designing something better. The result was an experimental car Rolls drove out of the Midland Hotel's carriage court (demolished in the 1930s to make way for a reception area) and realised that this 2-cylinder was as smooth and quiet as a 4-cylinder. Rolls instructed his partner, Claude Johnson to take on the Royce car, and negotiate for C S Rolls & Co

(Royce below)

to have exclusive rights.

The great engineer and the parsimonious aristocrat signed their agreement on December 23, 1904. Claude Johnson thought double-barrelled names had a ring to them, and made his contribution to the motoring lexicon, inserting a clause stipulating that the cars would henceforward be known as Rolls-Royces.

Later one of the 40/50 cars was painted silver and called The Silver Ghost. It was the fashion to apply names to individual cars, rather like ships. The title stuck, and the Silver Ghost remained in production for eighteen years. Phantoms, Wraiths, Shadows and Spirits followed. Rolls-Royces were always beautifully made although scarcely inventive, and never above taking somebody else's component (an automatic transmission from General Motors, or a patent suspension from Citroën) and adapting it to its own exacting standards. An engine from Munich, transmission from Friedrichshafen, even an aluminium body from Dingolfing, has not been entirely out of character.

In 1914 the Admiralty instructed Lieut Walter Owen Bentley of the Royal Naval Air Service to find out why its new French aero engines were overheating. By 1916 he had designed one himself the Bentley rotary

(below)

, which saw service in Sopwith Camels, and was used by the RAF until 1926.

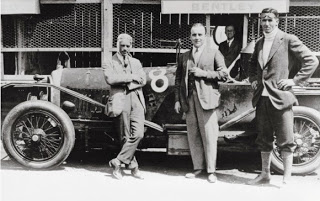

After the war Bentley wasted no time getting into car production. His 3 Litre appeared at the London Motor Show in 1919, yet the foundations of the Bentley legend were laid at the Le Mans 24 Hours race in France. Bentleys won it five times against opposition from Mercedes-Benz, Alfa Romeo, and Bugatti, but following the 1929 depression even the extravagant Bentley Boys had to economise. In July 1931 Bentley Motors called in the receiver.

Napier had not made a car since 1925, it was now predominantly an aero engine manufacturer, but was so impressed with the new 8 Litre opened negotiations to buy Bentley Motors. In September The Autocar confidently announced that an agreement only awaited formal approval. The receiver called for sealed bids, but the mysterious British Central Equitable Trust dashed Napier’s hopes. Weeks later the subterfuge was revealed. Rolls-Royce, learning of Napier's interest, had pre-empted its rival.

Bentley never forgave what he regarded as Rolls-Royce's deceit, and although he joined Bentley Motors (1931) Ltd soon left, forbidden from ever applying his name to a car again.

In 1933 Rolls-Royce announced the Derby-built Silent Sports Car, and with a few memorable exceptions, Bentleys became little more than badge-engineered Rolls-Royces. The exceptions included the splendid Continentals of the 1950s, with sweeping lines inspired by a contemporary Buick, and the new Continental developed by the VW-owned company. More in

The Complete Bentley also available as an ebook THE COMPLETE BENTLEY.

, Dove Publishing Ltd.

(right, WO Bentley bust at Bentley Motors, Crewe)