The re-creation of Mike Hawthorn’s Jaguar was a bit of a surprise. Old racing cars have been rebuilt following fatal accidents but usually using bits from the original. This is a calculated reconstruction of a car destroyed on the Guildford bypass on 22 January 1959. The wreckage was taken to Jaguar, broken up and, according to Rob Walker, burnt before being scrapped.

The re-creation of Mike Hawthorn’s Jaguar was a bit of a surprise. Old racing cars have been rebuilt following fatal accidents but usually using bits from the original. This is a calculated reconstruction of a car destroyed on the Guildford bypass on 22 January 1959. The wreckage was taken to Jaguar, broken up and, according to Rob Walker, burnt before being scrapped.

Remaking it seemed almost mawkish until I read how it had been done by my fellow Goodwood Road Racing Club member Nigel Webb, as a tribute to the 1958 World Champion. Opened in 2009 Webb’s private museum is devoted to Hawthorn’s memory and his cars include 774RW the 1955 Le Mans winning D-type, together with much Hawthorn memorabilia. It took ten years to build the Mark 1 saloon, replica of Hawthorn’s road car on loan from Jaguar. Only the original’s badge bar and keys remain. The DVLC refused to reissue the VDU881, the original registration, but Webb persuaded them to auction 881VDU.

Speculation about Hawthorn’s accident persists. How astonishing that the best driver in the world should be killed so inauspiciously. It looked so careless. There were theories about the handling of the Jaguar, about a non-standard throttle control, about the Dunlop Duraband tyres, about the rain-soaked road. None was completely convincing.

On 25 August 1998 Rob Walker talked to Eoin Young and me, on condition that we never revealed exactly what he told us until after his death. We had both known him from racing days; he had been a sort of neighbour of mine in Sutton Veny and Eoin and I visited him at his home in Nunney, Somerset. He was still in good health at 80 but died four years later from pneumonia. In 1959 Rob was driving his Mercedes-Benz 300SL on the same road, at the same time as Hawthorn.

Robert Ramsey Campbell Walker, of Frome, Somerset, garage-owner at Dorking, told the Coroner’s inquest in Guildford Guildhall, that at 11.55 am on that Thursday he was driving his Mercedes car from Somerset towards Guildford. He came along the Hog's Back road, then joined the Guildford by-pass.

He stopped at the link road junction to see what traffic was approaching. He had seen in his mirror a dark green Jaguar coming up behind. It had to stop behind him. He had no notion who the driver was.

Witness pulled away and soon the Jaguar came alongside, about opposite Coombs' filling station. "The driver seemed to equal my speed, turned round and gave me a very charming smile. I recognised Mike Hawthorn and turned and waved back."

Asked by the coroner what his speed was then, witness replied: "I haven't any idea. I was in second gear." The coroner: Are you telling me seriously you have no idea of your speed? Witness repeated that he had no idea. Continuing, he said the Jaguar's speed was increasing all the time. "As he passed me I slackened my speed. There was a great deal of spray around and I did not want to be too close.

“I suddenly saw the back of his car break away slightly when he was 30 to 50 yards away. I was very surprised because I couldn't see any reason for it. I didn't think much about it; it was a most normal thing to happen to him and I expected him to correct it. He did not slow at all.

“My impression is that his speed increased all the time and the car didn't correct at all, but the tail went out farther and farther, and suddenly I realised it had got to a state of no return, when even Mike Hawthorn could not do anything about it.”

Rob told Eoin and me: “I had a telephone call last week but I couldn’t hear who the chap was. ‘You remember me?’ he said. It’s terribly embarrassing when somebody says that. I sort of half did and half didn’t. His accent was somewhere between American and Australian then he said: ‘I’m the policeman who took the evidence from you after Mike Hawthorn’s accident’.”

Rob remembered more about the accident than the policeman had wanted him to. “I think they were a bit suspicious about him at the station. He used to drink with Mike. They knew each other well, because he took evidence on Mike’s father’s accident and he knew Mrs Hawthorn. The first thing he had said to me before the inquest was: ‘What were you doing?’ I said, ‘Well Mike came up alongside. I saw a Jaguar behind me coming down from the Hogs Back onto the Guildford Bypass. And I said I wasn’t accustomed to having Jaguars behind me, so I sort of accelerated on to the Guildford Bypass. He came up alongside and waved and I saw it was Mike Hawthorn. I said we were having a bit of a dice down the road.”

The police officer was aghast. Rob continued: “He said to me, ‘Don’t ever mention that word again in your life. It’s against the law to dice on British roads and if anybody hears you say that, you’ve absolutely had it’. Well, I thought, this is a good man. From then on we along pretty well. Afterwards he obviously realised he’d done me a good turn. He used to borrow a car every weekend from the garage, until I think the big boys got on to what he was doing. The chief of police came and saw me and asked, ‘Does he come over here often,’ so I said oh I’ve seen him once or twice. I didn’t say any more.”

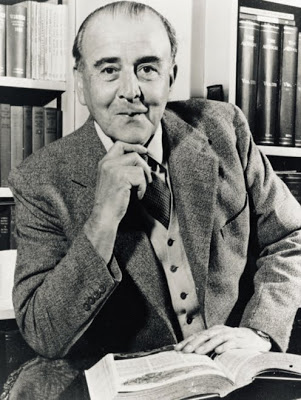

Goodwood tribute: Mike Hawthorn and Lofty England

Goodwood tribute: Mike Hawthorn and Lofty England

Rob told us the officer was seconded to royal protection duties before leaving the police and going to America, where he remained until his wife died in 1985. “He was about my age. I said to him ‘I’ll bet you one person who isn’t alive and that’s the gardener who saw the whole thing and guessed the speed.’ He said ‘Well you’re bloody wrong, he is. He’s 90 years old.’”

Eoin asked Rob if the gardener had told the court how fast he was going?

Rob: “Well, you see, one thing the coroner wanted was to get the speed we were doing. He wasn’t being spiteful. Obviously he had to establish some sort of speed so he asked me. I said well when I was driving in the wet I didn’t spend time looking at my speedometer. I said the only thing I can tell you is that I’d just changed into top gear, when Mike passed. In the 1950s going into top gear to most people meant 40 to 50 mph, but in the 300SL I never changed into top under100 mph. Sometimes a bit more. Of course I didn’t tell him that.”

The inquest found the gardener: “He lived up above the Guildford Bypass, looked down and he, I suppose said he was a witness because he claimed, ‘Oh I heard them going down the road - terrible noises they were making, absolutely flat out,’ to which the coroner said, ‘Yes well we don’t want to hear about that, how fast were they going?’ The gardener’s estimate was, ‘Oh, they must have been going at least 80mph.’ It was probably the fastest speed he’d ever heard of. This was absolutely ideal, because if he’d said any slower, nobody would have believed him, and if he’d said any faster they would have said what bloody fools we had been. So 80mph was written into the book and that’s what it always was.”

Rob told us he never opened the newspapers afterwards. “Michael Cooper Evans went through them all when we did a book together, and they’ve lain in that drawer ever since the accident. I didn’t want to look at them. I know some of them said pretty horrible things.

Rob’s policeman friend told him more things he hadn’t known at the time. Apparently somebody had been going to make a film about Hawthorn. This hand throttle that he’d fitted was going to feature as an explanation of the accident. The film makers wanted photographs of it but as a policeman he considered it his duty not to say anything about it. Rob was not sure he didn’t make a bit of money out of it.

“The account of the hand throttle is all written in Chris Nixon’s book

Mon Ami Mate. I asked if he (the police officer) had seen the hand throttle, and he said no, he hadn’t. He described what happened, ‘We put the remains of the Jaguar in Coombs’ Garage and we covered it with some sheet. The great mistake was that we didn’t put a guard on it all night. Somebody had been at it by next day.’ I asked did he think the person had removed the hand throttle, and he said yes he thought they had. He said another thing this person removed was Mike’s cap. That was definitely missing. Mike’s cap was very distinctive.”

Rob asked the policeman what had happened to the car. “Jaguar whipped it. They took it very smartly up to Jaguars, and this part I don’t know whether you can say or not because it is obviously very secret. He told me they burnt it.”

Rob discussed the accident with FRW “Lofty” England: “I’ve talked to Lofty about it many times, and he always sticks to the story of those Durabands. They held wonderfully in the wet, but when they did go they gave no warning whatsoever. Lofty said that’s what happened. What Nixon said in his book absolutely complies with what I said at the inquest. I told the Coroner’s court that the car was turned round and facing me, but the throttle was still wide open. I said I could hear the noise of it wide open. This seemed a most peculiar thing to me. But with a hand throttle it would be normal. And of course Lofty England and I completely disagree. Then the mechanic Nixon quotes in the book says that he fitted a hand throttle and somebody else who has interviewed him since says that he says he didn’t. The mechanic says he didn’t. Although Nixon said he told him that he did.”