New Year Resolution for car designers - reduce weight. Craftsmen coachbuilders knew how. They used aluminium. One of Rover's pioneering cars of 1903 had an aluminium backbone. After the Second World War, Rover turned again to aluminium although only under duress.

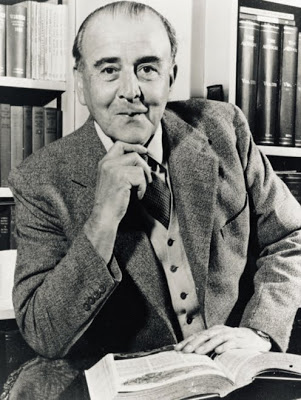

Rover's big Solihull factory started with steel car production, the first saloons off the production line in December 1946 made under strict government controls. In order to repay Britain’s war debts emergency legislation had been imposed forcing industry to earn money abroad. Steel rationing was strict, allocations were decided according to a company’s success in export markets, particularly North America. Spencer Wilks, Rover managing director since 1933, “strongly advised” the board in January 1945, “…that we should aim to expand our output, and that to achieve this we should not look primarily to our prewar models, but that we should add to our range by the introduction of a 6HP model.” An anomaly of the scarcity in materials and resources was that although steel was in short supply, aluminium remained plentiful, so Rover’s first post-war new car project was the M-type or M1 (above), a small 2-seat coupe made largely of aluminium. It had a 57mm x 68.5mm 4-cylinder 699cc 28bhp (21kW) engine that was a replica of the larger saloons’, with overhead inlet and side exhaust valves. It was thought that Solihull might make 15,000 fullsized cars and a further 5,000 M-types, so work began on an aluminium chassis, with a strong box-shaped scuttle for a car with a 77in (195.6cm) wheelbase and only 160in (406.4cm) long. Three prototypes were built and ran before the end of 1946, well-proportioned coupes with a distinctive Rover style, but by 1947 changes in car taxation and government pressure to adopt a one-model policy conspired against it. The M-type seemed unlikely to be sold in sufficient numbers to fill the vast factory acquired during the war so it was abandoned. It left a gap in Rover’s strategy, later filled by the Land Rover, and consigned the aluminium car to history for 50 years. Even the M-type’s spiritual successor, the inspirational Audi A1, found the going hard and its production life short.