Describing Ecurie Ecosse as a, “two-time Le Mans 24 Hours-winning squad” is as disingenuous as calling England FIFA World Cup winners. Ecurie Ecosse won Le Mans in 1956 and 1957, England the World Cup in 1966. I suppose stretching credulity is what publicists do. It’s nice to see Ecurie Ecosse racing again and I’m delighted it managed a “… solid finish” in the “challenging Blancpain Endurance race at Silverstone.” It races Barwell BMW Z4 GT3s and while 34th overall can’t match two Le Mans wins on the trot, it was probably quite hard work, “after battling tricky weather conditions at the British Grand Prix venue.” Not quite the debut win by Alasdair McCaig and Roger Bryant at Oulton Park, but satisfactory.

This is not the Ecurie Ecosse BMW. This is another BMW winning the 2010 24 Hours race at the Nurburgring

I don’t much envy Andrew Smith, Ecurie Ecosse’s publicist. Roy Hodgson, England manager, had a similar problem at the Donbass Arena when a French journalist quipped that England was no longer a major football power. “Of course we feel the weight of history," Hodgson said. "It was a facetious question but there was an element of truth in what he was saying. As a top nation we haven't won as many tournaments as we should or done as well as we should."

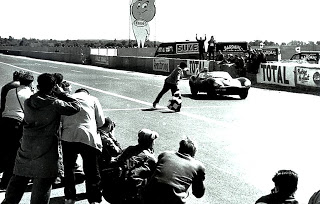

It was the same with Ecurie Ecosse. Founded in 1952 it was well presented, highly competitive and successful. Winning Le Mans barely four years later, almost the only private team that ever managed it, was astonishing even with covert support from Jaguar. It was, alas, downhill from then, except for a few minor triumphs such as almost inventing (with John Tojeiro) the mid-engined coupe and spotting the potential of both the Buick V8 and Jackie Stewart.

Nearly all that 1950s “squad” are gone; David Murray the team patron, Wilkie Wilkinson, all the drivers Ron Flockhart, Ninian Sanderson and Ivor Bueb, although happily mechanics survive, Stan Sproat and Ron Gaudion, from whom I heard only the other week. He lives in Australia and endorsed some of the views I took in Ecurie Ecosse, David Murray and the Legendary Scottish Motor Racing Team (PJ Publishing 2007), about Wilkie, whose role as an engineering expert I thought much exaggerated.

Ron confirmed that Wilkie’s Snetterton crash in XKD 501 (MWS 301)was entirely his own fault and XKD 603 (RSF 303 second Le Mans 1957 was prepared by Ron and Stan Sproat, while 606 (RSF 301) the fuel injected 1957 winner, was rebuilt at the works. Lofty England would not countenance it returning to Edinburgh because he had no confidence in Wilkie. Likeable enough but self-serving, it was all very well Wilkie tuning MG carburettors with a stethoscope at the Evans’s Bellevue Garage in the 1930s. Twenty years later he was well out of his depth.

What a tangled web they wove.

Royce, railway engineer, a vocation shared with WO Bentley.

Royce, railway engineer, a vocation shared with WO Bentley.