James Bond had an Aston Martin as a company car, but when he was spending his own money, and not that of Her Majesty’s Secret Service, he had a Bentley. In Ian Fleming novels he had, “…one of the last 4½ Litre Bentleys with the supercharger by Amherst Villiers. Bond drove it hard and well and with an almost sensual pleasure.”

The DB5 (above with the original and best film Bond), in which he pursued Auric Goldfinger’s henchmen, was invented for the films. Ejection seats, concealed guns, bulletproof visors, the submarine Lotus, the ski-ing Aston V8 and the rocket-firing BMW Z8 were the work of special effects gadgeteers. Ian Fleming’s obsession with Bentleys began when Reuter’s sent him to report Le Mans.

Bentley had already won four times, but the 1930 race was spectacular, a duel between a 6½ Litre Speed Six driven by Woolf Barnato and Glen Kidston, and a 7.1 litre SS Mercedes-Benz. It was an unequal struggle. Yet to Fleming it was British Racing Green versus

Deutschland über alles

. Six Bentleys were up against a solitary Mercedes of Teutonic splendour and wailing supercharger, which lasted eight and a half hours before retiring. Team chief Alfred Neubauer said it had a flat battery but WO Bentley saw water and oil pouring out of the engine. Still, the great white racer, driven by Rudolph Caracciola and Christian Werner, left a deep impression on Fleming. Winning with the unsupercharged Speed Six proved the highlight of Barnato’s driving career. The sole winner of Le Mans on every occasion he took part, his three victories were ruinous for Bentley’s shaky finances. Barnato virtually owned the firm, but could not prevent its sale at a knockdown price to Rolls-Royce. Fleming re-ran the duel in

Moonraker

, 007’s 1930 4½ litre Bentley engaging in a thrilling pursuit of Hugo Drax’s Mercedes. They raced from London to the south coast and only treachery led to the Bentley being wrecked.

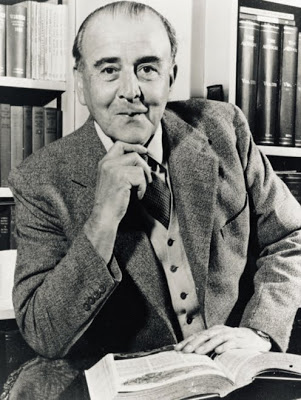

Superchargers fascinated Fleming and Amherst Villiers, the engineer who coerced WO Bentley into using them (see right). Bond’s cars sometimes had superchargers even when their real-life equivalents did not. He replaced the 4½ with another Bentley a, “…1953 Mark VI with an open touring body. It was battleship grey like the old 4½ Litre that had gone to its grave in a Maidstone garage, and the dark blue leather upholstery gave a luxurious hiss as he climbed in.”

Thunderball

, published in 1961, had Bond in, “… a Mark II Continental that some rich idiot had married to a telegraph pole.” Bond got Mulliner the coachbuilder (Fleming didn’t specify which Mulliner, but it was probably HJ) to rebuild it as a two-seater a bit like the late Lord David Strathcarron's (right).

He fitted a Mark IV engine with 9.2:1 compression, had it painted in rough, not gloss, battleship grey and upholstered it in black morocco. “She went like a bird and a bomb and Bond loved her more than all the women at present in his life rolled, if that were feasible, together.” The 007 of the novels was subtler. As Fleming’s alter ego Scottish-born Bond was successful with women, liked his Martinis shaken not stirred and was a superb golfer, gambler, lover and driver. His taste was impeccable whatever he drank, smoked, ate, drove or shot with. Fleming demonstrated his exquisite taste in a Rolex Oyster watch, Saxone golf shoes and Bond displayed complete mastery of unexpected skills. Being equal to any situation meant any old gun simply wouldn’t do. Bond used a Smith & Wesson .38 Centennial Airweight, and a Walther PPK 7.65mm with a Berns-Martin triple-draw holster. Fleming did not get his guns right first time and Bond had to change on instructions from “M”. A Glasgow gun expert Geoffrey Boothroyd pointed out to that no special agent worth his calibre would be seen dead with a .25 Beretta automatic. “A lady’s gun, and not really a nice lady”. Fleming repaid the compliment, portraying him in novels as Major Boothroyd, 007’s armourer. Later simply as “Q” Desmond Llewellyn played the role to perfection in the films.

In Fleming’s

Live and Let Die

Bond dismissed American cars as: “…just beetle-shaped dodgems in which you motor along with one hand on the wheel, the radio full on and the power-operated windows closed to keep out the draughts.” But his CIA friend Felix Leiter, “… had got hold of an old Cord. One of the few American cars with personality, and it cheered Bond to get into the low-hung saloon, to hear the solid bite of the gears and the masculine tone of the wide exhaust. Fifteen years old, he reflected, yet still one of the most modern cars in the world.”

Fleming was on shaky ground when he tried inventing a car. In Diamonds are Forever, Leiter introduced Bond to his Studillac explaining: “You couldn’t have anything better than this body. Designed by the Frenchman Raymond Loewy. Best designer in the world.” It was not complete invention. It was really a disguised Studebaker Avanti Fleming was coaxed into by the showy Loewy. The car was a disaster. I tested one in the 1960s, found Loewy’s plastic bodywork pretentious, and it suffered from nightmare axle tramp, slithering scarily in the wet on skinny tyres. An engraved plate reminded the driver that the tyres were suitable only for “ordinary motoring”. The Paxton belt-driven supercharger wafted a light breeze through the carburettor and it managed a perilous 120mph and 11mpg. It was no surprise Studebaker went out of business.

Bond must have been brave to cope with it, although Fleming thought it, “a bomb of a motor car. It cut my drive from London to Sandwich by 20 minutes, just on those Bendix disc brakes. The tremendous rattle of the exhaust note as that big supercharged V8 goes through maximum torque makes you feel young again.” The Avanti may have been a lapse of taste yet as a young reporter in the 1930s, Fleming had been devoted to cars. He owned a khaki-coloured “Flying” Standard, an unpromising start, but as a poorly paid journalist probably all he could afford. He was on firmer ground with the Bentley. The year after he covered Le Mans Fleming co-drove with Donald Healey in the Alpine Rally, winning their class in a 4.5 litre Invicta but in his later years Fleming grew cantankerous. Two women in a car, he averred, would sooner or later look into each other’s eyes. Cars with four women were dangerous because the two in the front would always turn round to those in the back. He disliked dangling dollies, tigers in the back window, steering wheel covers and string-backed driving gloves. He hated Ecosse plates, was against adorning a car with badges and would probably have regarded an Aston Martin as effete. My recommendation for Bond? Something like the Embiricos Bentley (below left) if he had to have a 1930s car. Or a worthy successor like the Continental GT Speed (below right). THE COMPLETE BENTLEY ebook