Jaguars inspired designers beyond Jaguar, but none had the certain touch of Sir William Lyons. Bertone, Pininfarina and Giugiaro never matched Jaguar’s founder for identifying Jaguar customers. They were Italian of course. Jaguars were essentially English and middle class. From sunburst upholstery and faux nautical ventilators of the 1920s SS, to lookalike Bentleys of the 1940s Lyons understood his clientele. He provided them with big headlamps and walnut interiors, good proportions and discreet understatement. Jaguars looked not-too-racy and in perfect taste. His skill rarely deserted him although he probably over-embellished his second thoughts. No XK 140 or 150 matched the purity of the XK 120. Later E-types never had the plain elegance of the 1961 original, much the work of aerodynamicist Malcolm Sayer.

It all went wrong with the XJ-S, also partly Sayer’s, and made uncharacteristically with advice from fashionistas, who encouraged square headlamps, and salesmen pushing Jaguar up-market.

Nuccio Bertone had a go in 1957 with a car based on the XK150. The effect was quite close to the Jaguar idiom and in 1966 he did a nicely proportioned 2-door coupe on an S-type saloon. It looked a bit like the Sunbeam Venezia by Superleggera Touring three years earlier launched, if that’s the word, with gondolas in Venice. Pininfarina’s 1978 XJ-S Spyder was a stretchy E-type and William Towns tried an origami one sadly no more successful than his knife-edge Lagonda.

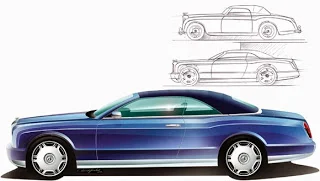

Giugiaro had a go in 1990 with the Kensington based on an XJ12 platform, shown at Geneva, which in my 11 March Sunday Times column I thought important. Jaguar style at the time was being obliged to address a wider market than the English middle class. Giugiaro occupied the high ground of automotive haute couture in 1990, with big commissions from the Far East as well as a series of VWs and Alfa Romeos in Europe. It was deceptive. Giugiaro was never into voluptuous curves and his Jaguar was heavy and rotund. Detailing was good. The grille and classically Jaguar rear window were fine but it remained a one-off. There was no encouragement from Jaguar, which regarded it very much as ‘not invented here’. Bertone tried again in 2011 with a slender pillarless saloon, the B99 hybrid.

The inhibitions designers face now make anything profound or distinctive in car design next to impossible. Crumple zones, pedestrian impact rules and headlamp heights are so constricting that anything ground-breaking is unlikely. Jaguar head of design Ian Callum’s hand is far more repressed than ever Lyons’s or Sayer’s was. Committees lobbyists and legislators, mostly now in Brussels, call the tune. Customers play second fiddle.

Pictures: (top) Sir William Lyons (left) with Tazio Nuvolari, XK120, Silverstone. (Top right) Bertone XK150. (left) Pininfarina XJ41. right Bertone's "Venezia" and left Giugiaro's Kensington. Below Pillarless hybrid at Geneva.