Something about MG brings out the best in people. Applause for winners at the Lincolnshire Centre MG Car Club’s concours wasn’t just polite. It had warmth. Classic MGs cover a wide spectrum. This was no Hurlingham with cars costing millions, nor a Bentley or Jaguar club affair with cars at hundreds of thousands. MGs can reach big money of course, yet ever since Cecil Kimber poshed up Morrises to make world-class sports carS, MGs have been unique. They are classy without being class-conscious. Some cars are classics because there weren’t many. MGs became classics even though there were lots.

Yesterday at the Concours I didn’t meet any owners who talked about what their cars were worth. Well, with one exception because I asked him. Not many seem to restore or refurbish MGs because of what they’ll fetch at Bonhams’ or how they’ll look at Goodwood, although some MG folk can be just as arcane about originality. The immaculate 1964 MGB had a notice in the window detailing its restoration to correctitude strictly in accordance with Anders Clausager’s Original MG book. It was apparently one of the last in the series with original recessed door handles and a 36-rivet grille where all the uprights were individually attached to the chrome surround. Now, there’s detailing.

A passing spectator wondered if its light blue was the best colour for a B and I tried to remember the colour of the first MGB I drove. This was a press car 523 CBL for the first official road test published in The Motor on 24 October 1962. I drove it from London to Charterhall, the Scottish Borders track, the weekend before the test was published, the badges taped over because it was still officially “secret”. Jackie Stewart was racing, probably FSN1 the Dumbuck Jaguar E-type and I parked the MG in a quiet corner of the paddock where it immediately became a focus of interest.

I’m not good with colours; I seem to recall it was blue. I had had an MGA, which a B could never match for precision and the 1962 test that I compiled (it was essentially a committee job by road test staff under Charles Bulmer and Joe Lowrey) now seems a little uncertain about the handling. It makes a lot of the ride and the stiffness (we’d now say over-engineering) of the body shell. “The rack-and-pinion steering has been freed from kick-back without flexibility or much frictional damping being perceptible, yet feel of the road is retained.” Faint praise I think.

Another car at the concours was MG 1199 (below left), an 18/80 looking like the twin of the late Roger Stanbury’s splendid open 4-seater MG1200 in which I suffered many happy adventures. The wind in Roger’s 18/80 not only blew in your hair, it also blew up through holes in the floor, a legacy owed to neglect of a car he bought as a student.

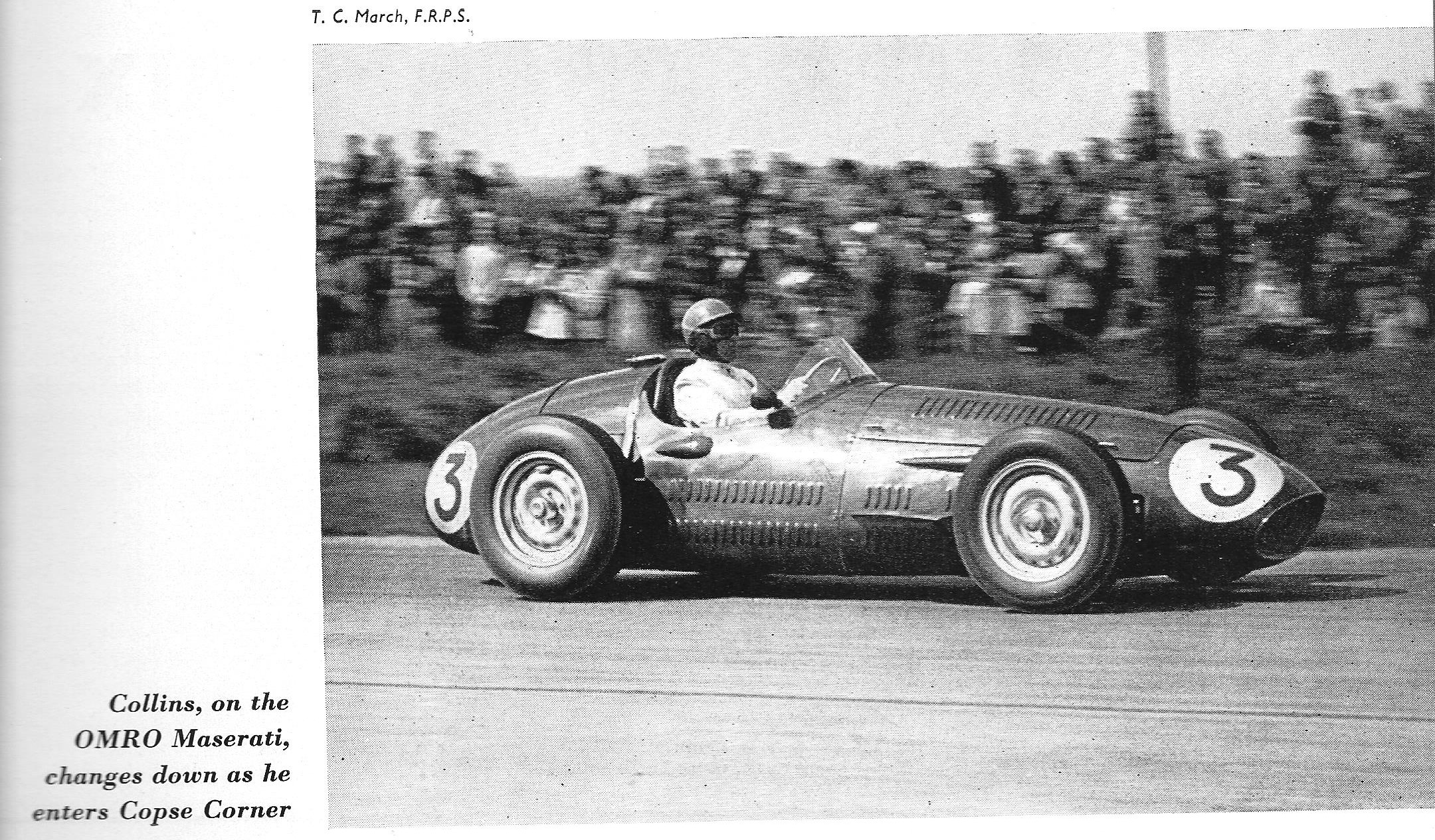

My affection for MGs began when, like many an 11-year old, I read about it in Circuit Dust and Combat, borrowed from the public library. Romantic and colourful, these tomes by Alfred Edgar Frederick Higgs, or Barré Lyndon as he preferred to be known fired the imagination. It was entirely fitting that Lyndon made his name as a Hollywood scriptwriter after lending MGs a dramatic quality and a legacy of myth and legend beyond the realms of anything so prosaic as a car.