MG gave away secrets to Japan. Four years after the sleek EX-E prototype (above) was shown at Frankfurt, I tested a Nissan 200SX. Austin-Rover was broke in 1985 and EX-E rests a museum piece at Gaydon, milk spilt in the dog days of British Leyland. A reminder of how inept politicians were at trying to run industry.

EX-E was not forgotten at Nissan.

Full accounts of all MGs in MG Classics Dove Publishing Books 1 2 and 3

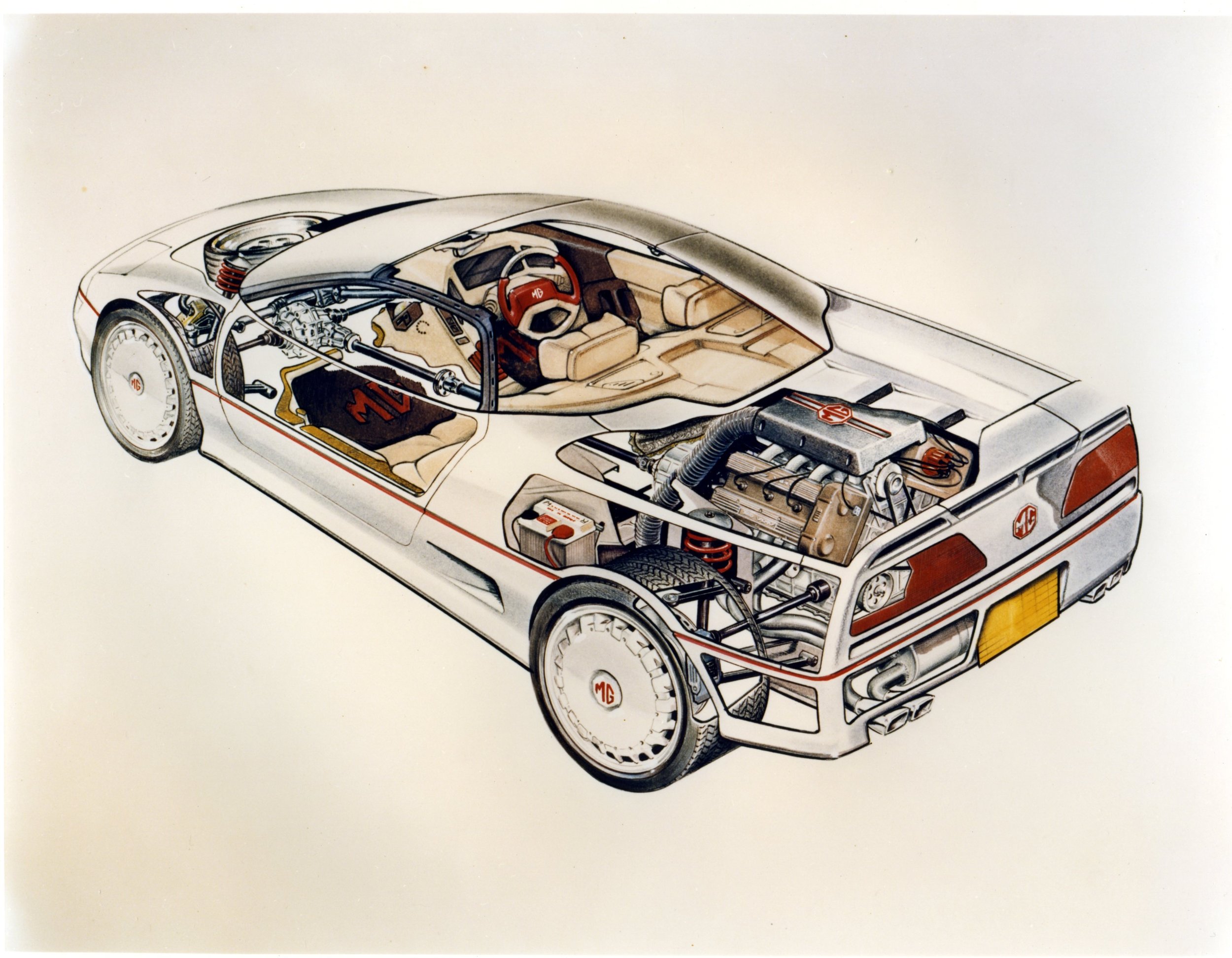

Roy Axe formerly with Chrysler and Gerry McGovern, who went on to design the MGF and Range Rover Evoque, were tasked with re-establishing MG. For EX-E they invented a way of making a completely smooth roof and flush windows, by bonding curved glass panels to the bodyshell. Darkened to conceal roof pillars it gave the effect of satin-black metal, creating the tear-drop profile of a jet fighter that had defeated a generation of car designers.

Left EX-E at Gaydon alongside PR3 and Old Number One. Centre cutaway showing mid-engine. Right well executed interior.

It was not to be. MG EX-E was junked and it was Nissan that bonded glass flush with the doors, curving it into the smooth body line of the masterly 200SX. It was not mid-engined, it was front-engined and practical, with two small rear seats and sufficient luggage space for a small sports car.

The 200SX was not brandished and then shelved. It was designed, developed, put into production and sold for £17,000 in Britain where cramming production-line engines into small sports cars was pioneered by Cecil Kimber of MGs in the 1920s. Nissan reoccupied MG’s middle market, 200SX’s top speed of 140mph took it into Porsche territory. It matched the speed and power of the Porsche 944 for £9,000 less and although it did not have a galvanised rust-free bodyshell, nor the smoothness and refinement of Porsches it had their appearance and pace.

The Japanese made great-looking engines and the 200SX, 1.8 litres, four cylinders, double overhead camshafts with four valves per cylinder was no exception (see below). This would have been the specification of a racing engine a few years before. It had fuel injection and a turbocharger with an intercooler when rivals didn’t. There were no dangly plug leads. It looked the part. A direct ignition system put a tiny coil directly above each plug, firing each electronically at low voltage. Eliminating tiresome high-tension leads had never occurred to Austin-Rover.

The 200SX had exemplary handling and a smooth ride. All it lacked against European thoroughbreds were elusive ones of texture and touch. The steering was a bit languid; it didn’t notify the driver of bumps and surfaces and slippery patches the way a Porsche or a Lotus did. In the end it didn’t matter; the 200SX was one of the best-roadholding sports cars ever from Japan, matched only by the MR-2 from Toyota. It was practical, plain inside yet businesslike. The boot space would have been larger had the British accepted a space-saver spare wheel, perfectly legal and eminently practical, but inadmissible following suspicion encouraged by the AA.

My test car (below) was an automatic, which I didn’t much like. Not entirely satisfactory for a sports car at the best of times, it kept hunting up and down for suitable gears, the engine revving wildly one moment then slogging below speeds where the turbo boosted power. It was not a particularly agreeable-sounding engine and progressing by short, noisy leaps made the manual gearbox seem a better, cheaper alternative.

Its brakes were also unsatisfactory, heavy use left them fading badly, wreathed in smoke and smelly; I should not have liked to rely on them for dashing down an Alp. I challenged Nissan about them and it claimed the car had been used for brake testing, wearing out the friction pads.

Caveats apart, however, this was a masterpiece of a sports car and indicative not only of the tragic collapse of MG following the Abingdon factory closure in 1980, but also of how a weakling British motor industry management discarded its own skills. In the end it even exported the marque itself, together with nearly 100 years of history, to the Chinese.